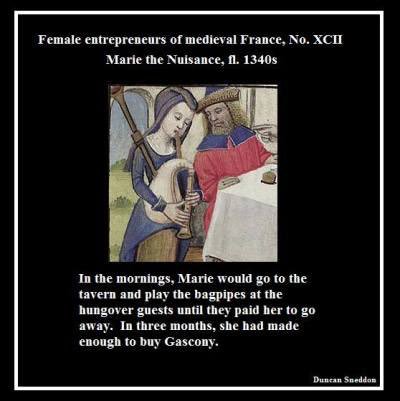

This post was originally a thread which I posted on Twitter in March 2019, in response to a meme which was being widely linked to on social media during that time. Since Twitter’s long-term resilience is far from assured, and since the “Marie the Nuisance” image is still being presented as accurate history in various places online, I’m reproducing the thread’s info in an expanded form here.

As a historian of medieval women, I can understand the allure of memes like the one below. That allure is why this image could be posted on Twitter by a popular history author with the caption “This woman is both my hero and history’s greatest villain” and get more than 28,000 likes (as of January 2023). I talk about it a lot with students in my women’s history course: how powerful the desire can be to find women in the past achieving things despite the odds; the hook of “hidden” or “secret” histories.

But Marie isn’t a go-getting woman unfairly left out of the history books because of patriarchal gatekeeping, as some of the social media responses to this meme asserted. There’s a much simpler reason why Marie the Nuisance doesn’t show up in the history books.

Marie never existed.

There’s a popular misconception that professional historians conspire to bury the truth about the history of women or other historically underrepresented groups. This is untrue. Just because secondary school textbooks or History Channel documentaries (or at least, the documentaries that the History Channel used to show back before it just turned into a showcase for Nazi alien ice road truckers building pyramids or what have you) tend to sideline women doesn’t mean that there aren’t lost of historians out there producing great works of women’s history and also centering women in their teaching.

Hundreds of books have been written about medieval women in the past 30 or 40 years alone, and surely thousands of journal articles—all works that historians would love for more people to read rather than making sweeping assumptions about what historians do or about the passivity of women in the past!

And I can guarantee you that if there was evidence for the existence of a famous woman musician in medieval France who earned a good living from her work (even if not quite enough to buy Gascony; that’s a pretty big chunk of what is today France), some historian would have written about her.

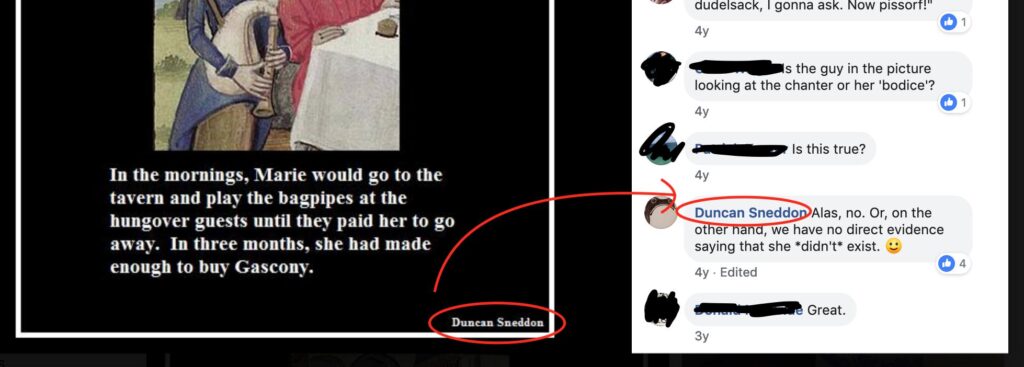

The most cursory search online shows that references to Marie the Nuisance appear only on English-language meme/social media sites. She has no presence on the Francophone web, despite being ostensibly from what is today France, and there were no references that I could find in any academic writing. But look back up at the bottom right-hand corner of the image: there’s a name.

Searching for the image together with that name shows that this is actually a years-old joke among a group of friends on Facebook. (The text reads “Is this true?” “Alas, no. Or, on the other hand, we have no direct evidence saying that she *didn’t* exist. :)”)

In the grand scheme of things, this of course all fairly harmless. It’s not hurting anyone to imagine a badass bagpipe-playing woman in 14th-century Europe.

But it does speak to bigger concerns about information literacy and the reduction of women’s history to “Go, Girl!” anecdote. There’s just so much evidence out there for actual medieval women entrepreneurs whose stories are well worth the telling, even if they lack a catchy punchline or any clear subversion of societal expectations. Women like Alice Claver, a silk mercer (dealer) who supplied fabric to decorate Edward IV’s books and the mantle laces for the coronation robes of Richard III and who earned a fortune big enough to purchase a large house in central London; or the dozens upon dozens of women who worked in the silk trade in medieval Paris; or Licoricia of Winchester, who was one half of an entrepreneurial power couple and who hobnobbed with royalty in thirteenth-century England; or Venguessone Nathan, who was one of the largest landowners in fifteenth-century Arles, and who on her death left substantial bequests to her synagogue for charitable purposes.

We sadly know little about these women, and none of their lives lend themselves easily to sloganeering or meme creation. But unlike Marie the Nuisance, they lived, and they worked, and they were important parts of their families and communities. They should merit our attention.

And what about that manuscript image itself, which purports to show Marie with her bagpipes? A little online digging shows that it’s actually a depiction of a feast from a copy of the Roman de la Rose, an allegorical poem about courtly love which was wildly popular in late medieval Europe. The poem is pretty misogynistic, and the Douce Roman de la Rose, unlike some other extant copies, was illustrated by a man rather than a woman. A bit of a letdown, perhaps.

But who was this manuscript made for? It was almost certainly commissioned by Louise of Savoy, an immensely powerful woman who was a significant patron or the arts and who was twice regent of France in the early sixteenth century—a woman who definitely didn’t need bagpipes in order to let her voice be heard.

I just stumbled across the very meme you are talking about, and obviously Googled it to see if it was, hopefully, true. Was immediately led to this article which was both fascinating and beautifully stated. Thank you!

I’m here for the same reason as Steve😄

I have no disagreement with the author’s point that historical women get short shrift in academia and in “real life,” but what struck me was the rest of the unspoken narrative: That we have become so historically ignorant AND humor impaired that we cannot recognize absurd historical juxtapositions for what they are.

I think there are many roads that have brought us to this place, some more culpable and perverse than others, but I’m reminded of Susan Sontag’s comment: “Our failure is one of imagination, of empathy: We have failed to keep this reality in mind.”

She was writing about the barrier destroying photographs of war that in its time forced the world to confront global, political violence; but I think her words also show our inability to recognize ironic humor from the “noise” of cacophanous social media.

And borrowing from Herman Hesse’s “Glassbead Game…” these are once again the days of the fuilleton, the ephemera of a society that has no desire to think critically but would rather be blown about by freshets of juicy gossip and pseudo-earnest disagreements about science, mathematics, “socialism,” and whether we should be vaccinated…

* S. Sontag

Regarding the Pain of Others

Picado (2003)

I came across this site for the very same reason. I took it as a joke but wanted to know if the artwork was authentic. Proof that you can google almost anything on the internet and find a website about it. 😆