Many migrants know the experience of returning to your homeplace after months or years away and being struck by some change, large or small, that’s long since been absorbed by everyone around you. An empty shopfront now houses a coffeeshop; new homes are being built where there were once green fields. One of the things that were new to me when I was back in Portlaoise—my hometown in the Irish Midlands—earlier this year was a set of historical markers that have been placed around the town. As Irish towns go, Portlaoise isn’t particularly old—it was founded in the mid-16th century—and it doesn’t boast the kinds of historic buildings that generally draw the tourist cards and warrant these kinds of signs. I can’t remember being raised to think of it as a place with any momentous history to it, and on the rare occasions the town appeared in the news it was generally in relation to its prison.

But Portlaoise has expanded enormously over the last 30 years, and now we have historic signs, a McDonald’s, a Jysk, and more coffee shops than you can shake a stick at. Growth!

In all seriousness, it’s great to see investment in recording local history and educating people about it, but I found myself standing in front of the signs and wondering about the choices that went into how they frame the town’s history.

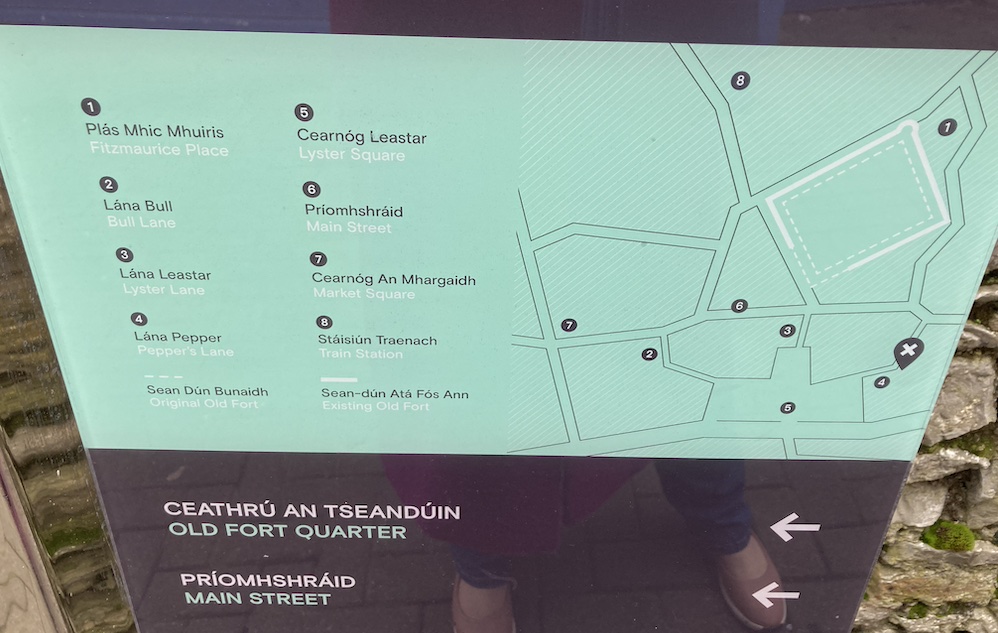

There’s only so much text you can fit onto a single sign after all, and choices have to be made. And I’m not disputing anything in the two paragraphs we get here about Pepper’s Lane—to the best of my knowledge, they fits just fine with what map and archaeological evidence we have. But it’s the framing of it—and implicitly the other centuries-old short, narrow streets which run south from Main Street, Bull Lane and Lyster Lane—as one of Portlaoise’s “medieval lanes” which gave this historian of the Middle Ages pause.

Since when has Portlaoise been a medieval town?

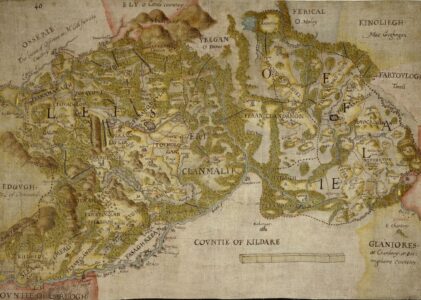

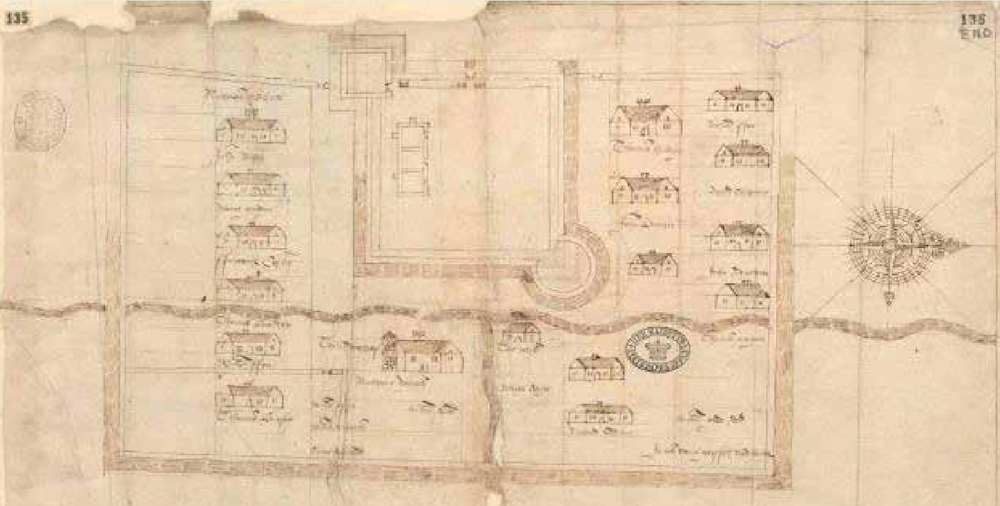

Portlaoise began as a settlement around a British military fortification—referred to variously as “Fort of Leix”, “Fort Protector”, or “Campa”—in the 1540s. There’s no archaeological or documentary evidence that I’m aware of for any pre-existing medieval settlement on the site, whether Gaelic Irish or Anglo-Norman. One of the earliest pieces of evidence we have of Portlaoise’s history is a map dated ca. 1570 which shows what seems to be a regular, planned settlement of houses arranged around the fort. Each structure on the map is labelled with the name of its owner and their surnames—Harding, Chapman, ap Robarte, and so on—seem to indicate recent English or Welsh origins.

In other words, the fledgling Portlaoise was one of the one of the larger settlements which was established during the Plantation of Ireland, a process of settler colonisation which aimed to transform Ireland’s ethnic, cultural, and religious landscape, while also permanently altering the nature of its relationship with the British Crown.

Now, there isn’t one fixed date you can point to as the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the early modern period, but I tend to agree that “if you can see Protestants you’ve gone too far.” Portlaoise is an early modern foundation, not a medieval one, and so its laneways definitionally cannot be medieval.

So why frame it as such?

My suspicion is that it comes down to marketing. “Medieval Portlaoise” is a concept that seems to emerge around the same time as that of the “Old Fort Quarter” and its accompanying festival. (The “Old Fort Quarter” means, I think, the area to the north of the Main Street roughly between Church Street to the west and Church Avenue to the east. I say “I think” because this isn’t a term that any regular person ever actually used; my late grandparents would be baffled by it.) The Old Fort Quarter Festival bills itself as a “heritage event”, but its programme is heavy on the medieval armour and Viking warriors—nothing, in other words, that really has a connection to the actual history of the town of Portlaoise.

I imagine that it’s easier for most people to conjure up a mental image of a knight from the Middle Ages than it is a seventeenth-century merchant adventurer. “Medieval” is a more marketable concept, and frankly a more comfortable one—imagining knights on horseback is fun; contemplating territorial dispossession and linguistic loss is not. It may be more palatable to walk past a set of heritage signs that tell you that your town is medieval—which for many people is probably equivalent to calling it immemorial—than to think of it as a more recent colonial imposition on the landscape. (And perhaps, too, to think of at least some of your ancestors as non-Irish colonisers.)

There is an irony to this attempt to gingerly grapple/not grapple with Portlaoise’s deeper history. Like many Irish towns, Portlaoise is now ringed by clusters of newly-built roads and housing estates which tend to boast blandly aspirational, Anglicised names that overwrite the existing linguistic landscape: names like Fairgreen, Berryridge, Bellingham, Quail Run (!), Maryborough Village. That last is the one that really threw me the first time I saw it a few years ago.

Maryborough (pronounced Mar’bra) was the town’s name until the 1920s, when it was renamed Portlaoise—and Queen’s County was renamed Laois—as part of the decolonisation process following the establishment of the Irish Free State. Maryborough and Queen’s County were names given in honour of Mary I of England: as blatant an assertion of colonial hegemony as you can get.

Now right on the outskirts of modern Portlaoise there’s a large sign trying to entice you to come in and view the estate showhouse with text proclaiming “Maryborough Village, Portlaoise, 1557.” This date, of course, is not when the builders broke ground on the housing estate. It’s the year when Maryborough was established as the shire town of Queen’s County following an act of parliament which also legally displaced the ruling Gaelic Irish O’More clan of their territory. I don’t think most people would know that off the top of their head, but that’s not the point. The point is to conjure up some vague history for what was, until a few years ago, some fields in a townland called Clonroosk Little—to give it the patina of age and of something like heritage.

It’s always a little disorienting for the migrant to revisit their homeplace and find that its present no longer matches the picture you had in your head. It’s something else to find that its past doesn’t, either.