There are lots of attention-grabbing items on the news these days, but few have me double-take as effectively as a throwaway bit on one of the BBC World Service’s bulletins last night (17:56 mark). But a quick online search showed me that I hadn’t imagined it: there are indeed some scientists out there who are claiming that “historical biomolecules” found on a medieval document will give them the raw material they need to better understand the “environmental conditions, health, lifestyle, [and] nutrition” of Vlad Țepeș, a fifteenth-century ruler of Wallachia. (If that name rings a faint bell for you, it’s because Vlad has achieved a degree of modern fame as Vlad the Impaler, a likely inspiration for Bram Stoker’s Dracula.)

This is a bold claim indeed!

I can claim no expertise in biochemistry, so I’ve no ability to assess these scientists’ claims about extracting trace/contact organic materials from old paper or parchment. In fact, they almost certainly can. Similar kinds of projects in the past have revealed some fascinating things about, say, usage patterns in medieval manuscripts—the dirtier the edge of a page in a prayerbook, the more frequently readers likely turned to it, and the more likely they found the prayers on that page a particular comfort or especially efficacious.

But I’m dubious about the specificity of the claims that are being made here—that any biomolecules found can tell us something about one particular person—and about how they don’t seem to take into account what we know about how documents were made in the Middle Ages.

First, think about any news story you’ve ever come across about a criminal trial that relies on DNA evidence. Is it likely that anyone would ever be able to claim beyond a reasonable doubt that any trace biomolecules on a contemporary document that had been handled by several different people came from one of them in particular? Now think about how much more difficult it is to make a similar kind of evidentiary claim about a document that’s more than 500 years old. How can we know that any of these biomolecules were left specifically by Vlad and not by any of the dozens of people who’ve handled the document in the centuries since it was made? As I said, I’m not a scientist so I don’t know if any of these trace biomolecules contain DNA that could be compared against Vlad’s genetic profile to see if they’re a match—but since we don’t even know where Vlad was buried, that’s kind of a moot point.

Second, it’s not clear why this group of scientists thinks this document in particular is more likely than any other created during Vlad’s rule to contain any touch biomolecules from whim. What makes this one the prime candidate for this kind of historical analysis?

Third, and for me the most troubling, is how the scientists’ approach doesn’t seem to take into account how documents were created in the Middle Ages.

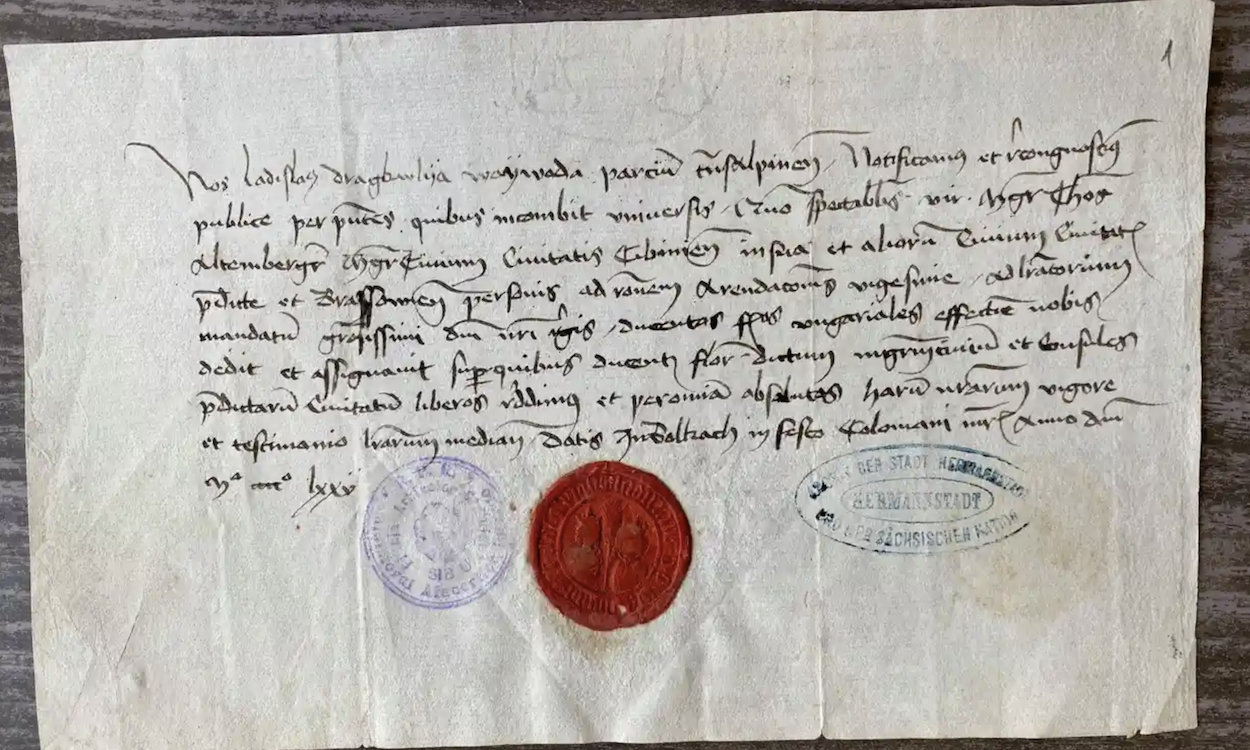

In the news coverage so far, the scientists have referred to this document as a “letter”, and moreover one which was written and signed by Vlad himself. Except it at first glance to me fits better into the category of charter, a kind of administrative text, than it does a letter. While it has Vlad’s seal on it, it’s not signed by him, and I’d be really surprised if it was written by him as opposed to on his behalf. The text has all the hallmarks of the kind of routine, brief Latin text that a medieval ruler would let one of their scribes or chancery officials handle—just like civil servants today write much of the material produced by a given government ministry, rather than a minister sitting down to write it themself. There’s no proof that Vlad ever actually handled this document at all. If there is any historic trace material, I think it’s far more likely to come from a fifteenth-century scribe or from a nineteenth- or twentieth century archivist.

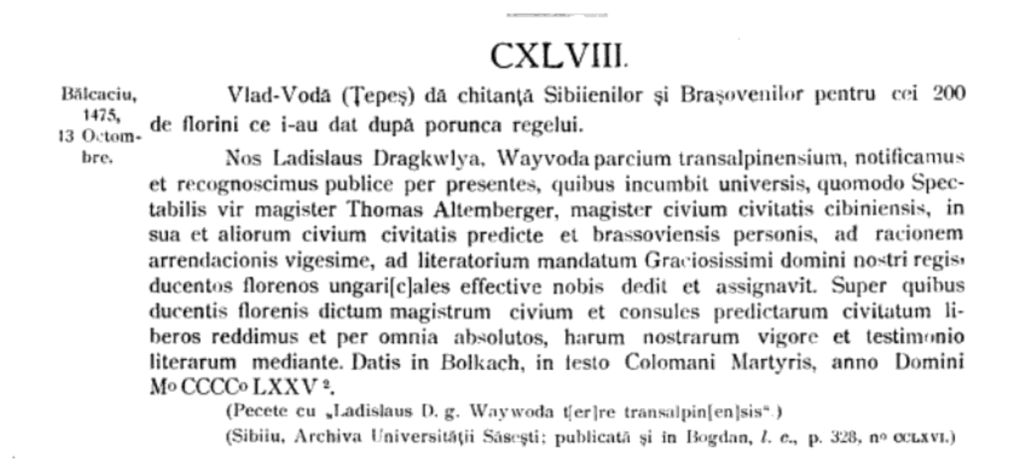

And we know for sure that the document was handled by such a modern archivist because a little bit of digging online turned up Volume 15 of Documente privitoare la istoria românilor (1911). This collection of transcribed historical documents includes the charter in question, and nothing in the text or in its accompanying notes indicates that it was a particularly unusual one.

(A sidenote: unlike the scientists’ description of it in the news coverage, the text seems to have been issued on October 13 (the feast day of St Coloman of Stockerau), not on August 4; it also appears to be about Vlad acknowledging the receipt of 200 florins from the people of Sibiu and Brașov, rather than a planned move to either city.)

New technologies have the potential to tell us a lot about the past—but they can only live up to that potential if they’re used with an understanding of and a respect for the solid body of historical knowledge and expertise that already exists.