The recent decision by several communities in France to ban the burkini has received a lot of attention around the world—and rightly so. It is a piece of legislation that is as poorly thought-through as it is self-defeating. As I stated in an interview with Sarah Bond, to mandate what a woman should not wear is no more feminist than to tell her what she should wear. Proponents of the ban claim that it will encourage laïcité, but limiting a devoutly religious woman’s ability to enter public space and move through mainstream secular society hardly seems like a logical way of encouraging social integration and cohesion.

Of course, France is not alone among European countries in passing or drafting legislation aimed at Islamic dress in its various forms. Legislators are often keen to stress that these laws are aimed at the emancipation of women, or are applied equally to forbid anyone, regardless of gender or religion, from covering their face in public. Yet the Catholic nun’s veil isn’t targeted in the same way, or an Orthodox Jewish woman’s head covering, and in fact most of the German states which have banned religious symbols and dress make explicit exemption in that legislation for Christian or Jewish cultural traditions. The Western debate over the burkini—or the hijab, niqab or burqa—is often less a conversation about women’s rights than it is using women’s clothing to make statements about identity and group morality.

There is a tendency in these debates to treat the veil as something distinctly other, as a symbol of something inherently non-European. Yet for most inhabitants of the medieval West, that view would have been a strange one indeed. No respectable woman past adolescence would have thought of leaving her home with her head bare, and the veil or headdress was the fundamental symbol of the married woman.

Medieval Christian views were shaped by scripture, such as the letter of Paul of Tarsus which stated that women should cover their hair while praying, and linked this mandate to women’s inferior status comparative to that of men. Over time, this admonition was applied more broadly. For a woman to have walked the streets of a medieval town with her hair uncovered would have invited suspicion as to her sexual morality—that was the behaviour of a prostitute. (In fact, if an “honest” woman from the French town of Arles saw a prostitute wearing a veil, she had the legal right to rip it off.)

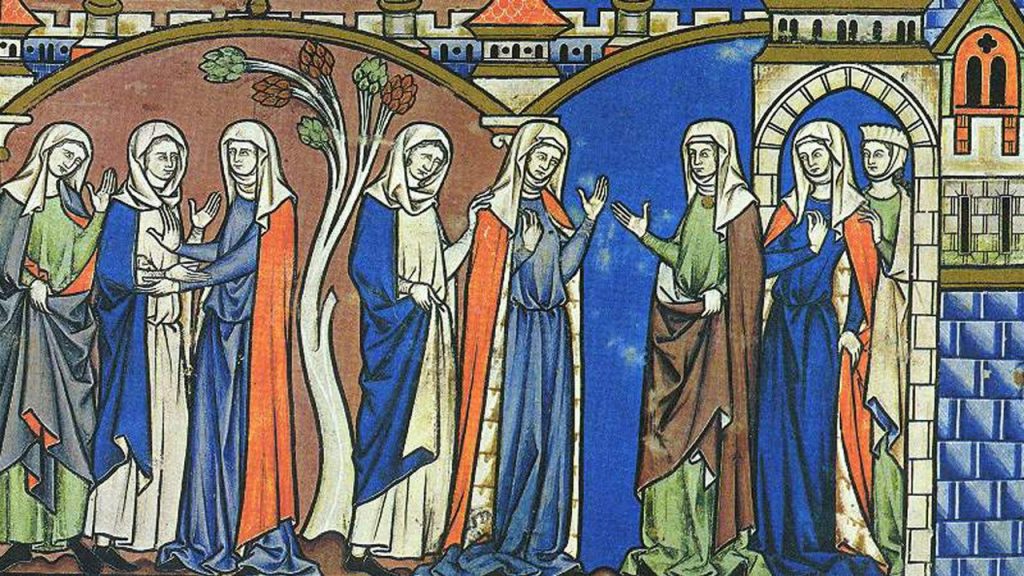

Most women would have used a fairly simple piece of cloth to cover their heads, but the more elaborate and fashionable headdresses form part of the visual language that we use to popularly identify the Middle Ages. The tall headdresses—either conical with a veil attached to the top or shaped into two horns—that were in vogue in the fourteenth- and fifteenth-centuries signal “fairytale princess” to most people nowadays. These headdresses were preceded by other styles such as the head-, chin-, and neck-covering wimple (10th to mid-14th centuries), the barbette and the filet (12th to 14th centuries), and succeeded by others like the low hoods and caps (15th and 16th centuries) familiar from portraits of Tudor women.

Medieval headdresses changed with fashion but also with life stage. A new mother wore a white veil when she was churched (underwent a purificatory ritual after childbirth); a widow wore a severe linen barbe which covered her hair, neck, ears and the upper chest. This meant that a woman’s head covering was a symbol of her morality, but also indicated her role within the community.

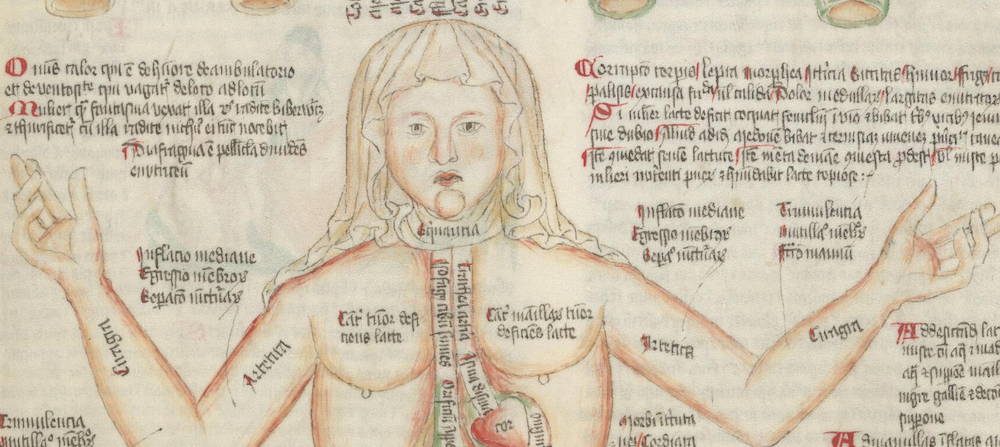

The veil was inextricably linked to the virtuous married woman in particular. We can see this by looking at the so-called Wellcome Apocalypse, a fifteenth-century miscellany originating in Germany. It contains a number of different texts in German and Latin on scientific, moral, and theological topics, and also a number of medical diagrams.

One of these diagrams, the “Disease Woman”, shows a kind of living cadaver—a pregnant woman who gazes out at the viewer, her arms and legs spread wide. She isn’t wearing clothing, and her chest and abdomen have been cut open, revealing her internal anatomy—as nude as a person can be. And yet she is still depicted wearing a headdress which covers her hair, neck, and ears. Her visual honour is therefore preserved, and viewers are assured that she is still a respectable woman.

While such head coverings signalled differences in class, age, and social standing, they were not necessarily clear-cut markers of ethnicity or religion. The twelfth-century scholar Shlomo Ibn Parhon described Jewish women in Spain as adopting the practices of their Muslim neighbours, covering “their faces with a cloth. And when they wrap it around their faces they leave a hole opposite one eye at the edge of the cloth, with which to see, for it is forbidden to look at women.”

Shlomo’s near contemporary, the travel writer Muhammad ibn Ahmad Ibn Jubayr, visited Sicily in the 1180s. He wrote that Christian women in the capital city of Palermo followed Islamic fashions even at Christmastime: they went out “clad in gold-colored silk gowns, wrapped in elegant mantles, covered with colored veils, with gilded brodequins on their feet; they flaunt[ed] themselves in church in perfectly Muslim toilettes.” These sources don’t seem to reflect any deep anxiety about the implications, political or otherwise, about such cross-cultural borrowings. For people across medieval Europe—Christian, Jewish, and Muslim—a woman’s head covering was simply a homogeneous, universal type of clothing.

Yet the vast majority of women in Europe no longer wear veils or headdresses. Fashions and tastes changed. As anyone who’s ever seen a film adaptation of a Jane Austen novel or an episode of the show Mad Men knows, bonnets and hats remained a part of daily life for most people in the West until the 1960s, but these head coverings were increasingly less a direct assertion of a person’s morality or social status. Headscarves lingered in some places, particularly in rural areas or in Catholic countries where women wore mantillas or other kinds of veils to attend Mass until the late 1960s; I can certainly remember my maternal grandmother knotting a headscarf under her chin before she headed out to the shops in the Ireland of the late 1980s.

Over time, the veil and other similar headdresses began to be seen in the West as a sign of greater than normal religiosity, rather than as a cultural norm. For example, during the French Revolution, veiled nuns were regarded not as virtuous, but as a symbol of a hated and outdated regime, and were the victims of both verbal and physical attacks. Few Christian denominations in the West, with the exception of small groups such as the Amish and some Mennonites, require that their female members cover their heads regularly.

Our clothing makes a statement about who we are, and about the social influences which inform the choices we make about our clothing. This is especially true when it comes to women’s clothing (as the current US presidential election has made repeatedly clear). Gendered clothing legislation also makes a statement: it turns women’s bodies into proxies for far broader debates about politics, the role of religion in public life, and group identity. Forgetting the European history of the veil makes it far easier for those debates to become divisive, rather than a means for diverse communities to figure out how to peacefully co-exist.

And at us in Turkey, the secular warriors declair that the veil is medieval katholik attitude and it should be a copy of that and has nothing with islamic rules in fact.

Pingback: History Carnival #160 | Frog in a Well

Pingback: The Antinomies of Gender and Sexuality in Skyrim | ofthemakingofmanybooks

dang showed what they knew