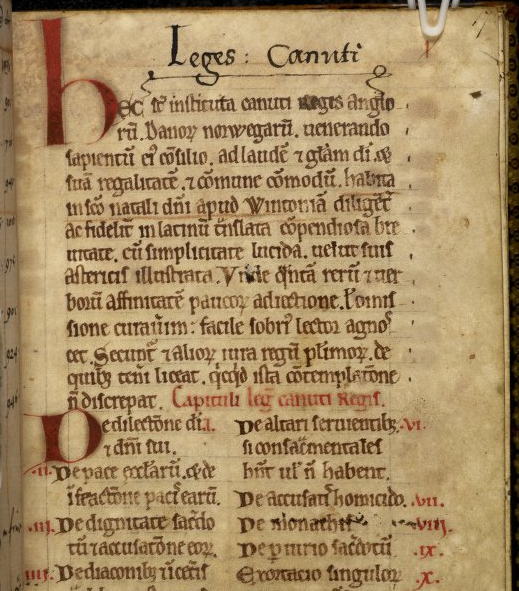

Image above: Holkham Lawbook. BL MS Additional 49366, f. 17r.

The Haskins Society Conference has moved this year to Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, the town motto of which is “Cows, Colleges, and Contentment.” I don’t think I saw any cows over the course of the weekend, but the latter two elements of the motto were there in abundance—as, sadly, were a number of late-night, grain-transporting freight trains on the track which ran right behind the hotel where most of the conference attendees were saying. I’ve never seen coffee consumed in such quantities as I have at this conference, and since I hang around academics for a living, that’s saying something.

Friday:

Presidential Address

“How English Laws Were Written”

Bruce O’Brien, Mary Washington University

Bruce O’Brien is one of the leaders of the Early English Laws Project, and his talk reflected the work which he has carried out as part of that project. He explored the dozen or so twelfth-century Latin translations such as the Holkham Lawbook (BL Additional MS 49366) and the Colbertine Cnut (BnF MS Lat 4771) which were (or which claimed to be) of pre-Conquest English law. O’Brien argued that since these texts go out of their way to stress their derivation from these earlier law codes—often incorporating Old English words in a deliberately different hand—they were using English as a kind of ‘tag’ of authenticity and a way of stressing the uniformity of custom.

Session 1: Crime and Punishment in Comparative Perspective

“Wrongs – Compensation – Revenge: The Eddic Poems as a Gateway to Viking Age Notions of ‘Crime and Punishment’”

Anne Iren Riisøy, Buskerud and Vestfold University College

The first session got underway with Anne Iren Riisøy’s exploration of the Eddic poems as a source of legal history, a facet of the corpus which she argued had previously been overlooked. She linked passages in the literature with archaeological finds. At Lilla Ullevi, for instance, an archaeological site north of Stockholm, some 65 iron rings have been discovered, dating 550-800. These bear a strong resemblance to the kind of rings with which compensation is paid in the poems, or on which oaths were sworn.

“Towards a Cultural History of Decapitation”

Alan Cooper, Colgate University

Narrative sources about the Third Crusade seem to convey a particular and intense fear of decapitation. Alan Cooper discussed the various factors, dating back to the mid-eleventh century, which he believes combined to create this strain of paranoia—a disdain for beheading as a “barbaric” practice of the Irish and the Scots; the uncomfortably intimate and often slow nature of decapitation as a method of execution in the Middle Ages; the associations with the biblical story of Judith and Holoferne; and Christian anxieties about the fragmentation of the body and its ramifications for resurrection and the afterlife. These particularly negative associations associated with this form of execution allowed it to feed into a hostile stereotype of Islam.

Narrative sources about the Third Crusade seem to convey a particular and intense fear of decapitation. Alan Cooper discussed the various factors, dating back to the mid-eleventh century, which he believes combined to create this strain of paranoia—a disdain for beheading as a “barbaric” practice of the Irish and the Scots; the uncomfortably intimate and often slow nature of decapitation as a method of execution in the Middle Ages; the associations with the biblical story of Judith and Holoferne; and Christian anxieties about the fragmentation of the body and its ramifications for resurrection and the afterlife. These particularly negative associations associated with this form of execution allowed it to feed into a hostile stereotype of Islam.

(If the success of a conference paper is measured in terms of number of call-backs to it by later speakers, this was surely the hit of the conference.)

[Image right: 12th-century ivory game piece, found at Bayeux, showing Judith beheading Holofernes. Credit.]

“Changing Legal Approaches to Adultery: The Evidence of the Fabliau Les Tresses”

April Harper, State University of New York, Oneonta

The thirteenth-century fabliau of Les Tresses is quite fabulously weird and disturbing and engaging—and, April Harper claimed, a source of socio-legal commentary about contemporary popular understandings of adultery. She claimed that the story worked as a pressure valve to discuss the legal state of wronged husbands, who had few desirable legal avenues to pursue when they had an adulterous spouse. As laid out by Harper, it’s a marvellously subversive piece of writing, and will ensure that you never look at a horse’s tail the same way again.

Session 2: Framing History: Re-presenting the Past in Word and Image

“Unlocking the Past: History, Theology, and Devotion on the Christian Franks Casket”

Katherine Cross, Wolfson College, Oxford and the British Museum

The Franks Casket is an eighth-century whale bone chest, currently held at the British Museum. Katherine Cross provided a really fascinating overview of its dense and complex decorative scheme. Some of its panels can still be read by us—the ones which show the adoration of the Magi, for instance, or Romulus and Remus suckling from the she-wolf—but others which seem to depict scenes from Anglo-Saxon myth are more obscure. No one has yet been able to decipher the full message of the casket, though Cross demonstrated how she thinks the artistic schema may have encouraged the reader to derive particular religious meaning from historical or mythical events.

[Pictured left: Franks Casket showing Wayland the Smith and Adoration of Magi scene. Credit.]

[Pictured left: Franks Casket showing Wayland the Smith and Adoration of Magi scene. Credit.]

“Foedus foedatum: Retrospectives (1016–1166) on Concord, Counsel, and Corruption in Post-Roman Britain”

Emily Winkler, University College London

Emily Winkler examined eleventh- and twelfth-century narratives on English history in light of shifting contemporary ideas of what it meant to be English. She argued that there’s a difference in how more distant kings were evaluated in comparison with those who had lived more recently; the more recent kings were more “English” and held more personally accountable for defeat or failure. Winkler suggested that this was because of a heightened, post-Conquest concern with what legitimised and justified a given monarch’s rule.

“Abbatial Patronage and the Cult of the Saints at St Albans Abbey”

Kathryn Gerry, Memphis College of Art

The three different abbotships of Paul (1077-93), Richard (1097-1119), and Geoffrey (1119-46) were each distinguished by different approaches to patronage. Using the Gesta abbatum monasterii Sancti Albani, Kathryn Gerry teased out the ways in which we can evaluate whether abbots undertook acts of patronage (such as promoting a saint’s cult or establishign a scriptorium) primarily out of self-interest or out of concern for the community as a whole.

Saturday:

Session 3: Dominus/Domina: Was There a Gendered Exercise of Power?

“The Biography of Emma ‘of Ivry'”

Charlotte Cartwright, Arizona State University

This was a really great piece of historical detective work. We know almost nothing about the life of Emma of Ivry (as Charlotte Cartwright has dubbed her), an eleventh-century Norman woman who was related to the ducal family both by birth and by marriage. We know that she married, had children, and eventually entered the Benedictine abbey of Saint-Amand. However, using charter evidence and deduction, Cartwright argued convincingly for Emma’s having used her familial connections to further her own goals.

“Distaff Dynastic Lordship? Evidence from the Conquest Generation”

“Distaff Dynastic Lordship? Evidence from the Conquest Generation”

Laura Gathagan, State University of New York, Cortland

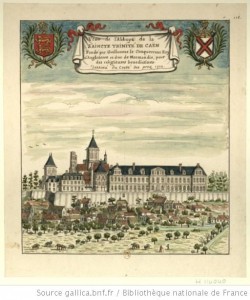

Laura Gathagan’s paper examined how patterns of administrative management could be passed from mother to daughter. Focusing on Adèle of Flanders, Matilda of Flanders, the Abbess Cecelia of Sainte-Trinité, and Adela of Blois, Gathagan showed how these women successfully marshalled their royal blood as a symbol of their legitimate right to wield judicial authority. Certainly, some of the charters of Matilda of Flanders from which Gathagan read excerpts show an incredibly detailed and careful managerial style, one which shows a woman who was intimately involved in even the minutia of donations made from her estate—a medieval micro-manager?

[Image left: Abbey of Sainte-Trinité, Caen (1702). Credit.]

“Lords or Ladies? Elisabeth and Eleanor of Vermandois and Succession, Governance, and Gender in the County of Vermandois”

Heather J. Tanner, The Ohio State University

Elisabeth and Eleanor of Vermandois are two figures well-known to those who work on women’s lordship. Heather Tanner argued that their respective careers show that for women to inherit and to rule was not in itself unusual in this period or this region—in fact, it was quite routine. Gendered differences in the exercise of power are seen more subtly in areas such as the age when it was considered appropriate for people to exercise authority. Boys could do so from their early teens, but girls could only do so once they were older.

Session 4: Reconfiguring Relics, Saints, and Authority After Conflict

“Holy Relics, Authority, and Legitimacy in Anglo-Saxon England and Ottonian Germany”

Laura Wangerin, University of Wisconsin

Despite the title, this paper focused mostly on Ottonian Germany, looking at how this dynasty used relics to create an ideology about their rule as well as to establish their legitimacy. It was through symbols rather through texts, Laura Wangerin argued, that the Ottonians established a link back to their Carolingian predecessors, primarily through their possession of the Holy Lance. This had supposed protective and thaumaturgic qualities and helped to create an idea of sacral kingship. (‘Thaumaturgic’ is one of my favourite words. It just has such a good mouth-feel.)

“The Fate of Anglo-Saxon Saints’ Cults After the Conquest: The Case of St Æthelwold of Winchester”

Rebecca Browett, Institute of Historical Research

Rebecca Browett looked at the cult of St Æthelwold at the abbeys of Abingdon and Winchester between 1066-1100. Æthelwold’s was a cult which never gained much traction outside of 10th century reform centres, and at Abingdon and Winchester (at this period under abbots of Norman origin) his veneration was actively discouraged for political reasons. Browett argued, I think convincingly, that this kind of study—looking at cults in multiple sites rather than focusing on their veneration in one particular place—is one which must be undertaken more often. Historians have tended to focus too much on individual sites when exploring the fate of Anglo-Saxon saints’ cults post-1066, rather than looking at them holistically.

“Helena, Constantine, and the Angevin Desire for Jerusalem”

“Helena, Constantine, and the Angevin Desire for Jerusalem”

Katie L. Hodges-Kluck, University of Tennessee

The historical connections between Helena, Constantine, and Britain are slight at best (Constantine was acclaimed emperor at York in 306), but as the English became more involved in the Crusades from the late twelfth century onwards, so too did they become ever more interested in Helena and Constantine. Helena acquired a spurious Anglo-British ancestry (she was actually from Anatolia), which Hodges-Kluck argued helped to collapse the temporal barrier between Roman Britain and Angevin England, linking it with the glories of the empire, and made Britain appear a more central part of the (Christian) Roman Empire.

[Image right: Statue of Constantine outside York Minster. Credit.]

C. Warren Hollister Lecture

“Rural Settlement in Roman Britain and Its Significance for the Early Medieval Period: New Research and Perspectives”

Martin Millett, Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge

Martin Millett was co-opted from his usual role as a professor of classical archaeology for the purposes of giving one of the conference’s keynote speeches on early medieval British domestic architecture. He looked primarily at the site of Cowdry’s Down in Hampshire, which he helped to excavate in the late 70s. It’s a seventh century site which has buildings that show evidence of a pattern of complex hybridisation, with both indigenous British and continental European influences. He then brought in comparative evidence from the Roman Rural Settlement in Britain project, which is showing a far richer and more varied landscape than was previously thought. I particularly liked Prof. Millett’s emphasis on there being no one Roman Britain in terms of material culture.

Session 5: Object Lessons: Material Evidence for Early Medieval Britain

Session 5: Object Lessons: Material Evidence for Early Medieval Britain

“Recycling Roman-ness in Fifth-Century Britain”

Robin Fleming, Boston College

This was a really enthralling run-through of the finds found at several different post-Roman sites in England—Cadbury Congresbury, Somerset; Baldock, Hertfordshire; Barrow Hills, Oxfordshire; and Shadwell, now part of London—which demonstrate reuse of Roman items over many generations. Once the Empire pulled back from Britain, the island underwent a drastic change in material culture as many skills such as pottery-making disappeared. Robin Fleming argued that we can more profitably understand the peoples of fifth-century Britain by thinking of them in relation to modern people who make a living scavenging from dumpsites than we can by studying the few surviving narrative sources for what they can tell us about politics. One of the most poignant finds from Baldock shown by Prof. Fleming was the pot seen to the left [Credit.] This was an extremely-worn beaker, produced during the Roman period, which had clearly been much used and carefully preserved by its owners for at least fifty years. It may well have been a family heirloom—and it was unearthed from the grave of a small child, a poignant testimony both to a family’s grief and their determination to honor their child as best they could in the manner of their ancestors.

“Sitting on the Fence: The Staffordshire Hoard Find Site in Context”

David Roffe, University of Oxford

There can’t be a historian or archaeologist out there who hasn’t heard of the Staffordshire Hoard find, and David Roffe attempted to put the hoard into its contemporary political context. Through a painstaking reading of Domesday book evidence, Roffe argued that it was not deposited in a marginal location, but rather one which was on the edge of a royal estate and in an area of symbolic importance within a wider seigneurial landscape.

Session 6: The Scripts of Robert of Torigni: An Inquiry in Conjectural History

Thomas Bisson, Harvard

Erik Kwakkel, Centre for the Arts in Society, University of Leiden

Patricia Stirnemann, IRHT, Paris

Benjamin Pohl, DAAD Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Cambridge

This was a roundtable discussion about the possibility of identifying which manuscripts from Mont-Saint-Michel may be in Robert of Torigni’s own hand. It involved comparative examinations of some 30 different manuscript folios, and so doesn’t allow for easy summarising. Let a picture be worth a thousand words, perhaps?

Sunday:

Session 7: The Perception and Practice of War

“The Semipagano Tiranno – Rethinking the Perception of Muslim Soldiers under Roger II”

“The Semipagano Tiranno – Rethinking the Perception of Muslim Soldiers under Roger II”

Joshua Birk, Smith College

Sunday morning’s sessions began with Joshua Birk’s paper. He refuted scholars who project thirteenth-century polemics against Muslims back onto the twelfth century. References to Roger II of Siciliy as Semipagano Tiranno, he argued, arose not from Roger’s employment of Muslim soldiers, but rather to the barbarous way in which Roger treated his Christian subjects.

[Image right: Roger II shown crowned by Christ in mosaic from La Martorana. Credit.]

“Trouble in Tripoli: Civil War and the Beginning of the End of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1277–1282”

Jesse Izzo, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Jesse Izzo’s paper moved further east, looking at the origins of the civil war which brought about the end of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. He sought to push those origins back two generations, when a marriage to a member of the Italian Conti family brought an influx of Romans into the kingdom. This shift in the balance of the ethnically western European inhabitants of the region was an antagonistic one, and helped exacerbate the situation when Bohemond VI died in 1275 leaving only a minor heir.

“Military Entrepreneurs in the Armies of Edward I of England (1273–1307)”

David Bachrach, University of New Hampshire

This was a very neatly argued look at the pay accounts of the armies of Edward I—a mostly overlooked and unpublished resource which nonetheless allows for the prosopographical study of those soldiers who were below the rank of gentry. David Bachrach contended that contrary to expectations, many of these men—whom he termed an “armigerous sub-gentry”—were military entrepreneurs who invested in horses and volunteered to fight because they saw entering the military as a viable career.

Session 8: New Approaches to the Naturalism of the Twelfth-Century Renaissance

“Naturalism Beyond Mediation: William of Conches and Hildegard von Bingen”

Willemien Otten, University of Chicago Divinity School

The last session focused on issues of nature and naturalism in twelfth-century writing. Willemien Otten began with a look at the writings of William of Conches and Hildegard of Bingen, two writers whose works are rarely directly compared. However, Otten argued, both conceive of nature as a conduit for the divine, and this is an idea which is very present in their work. In particular by looking at ideas of nature in Hildegard’s work, we can get a better sense of how her writing fit into broader intellectual trends of the twelfth century.

“Videmus nunc per speculum: Toward a New Paradigm for Twelfth-Century Naturalism”

Jason M. Baxter, Wyoming Catholic College

Jason Baxter’s paper looked at the Commentum super Martianum Capellam (University of Cambridge Library Ms 1.18), a work which is generally attributed to Bernard Silvestris. This is a work of synthesis, but one which posits that the natural workings of the world are a form of revelation, and fits in with what Baxter argues is a contemporary trend towards “natural mysticism”, seeing the invisible make itself visible in the natural order.

“Cosmogony, Mythology, and the Poet’s Persona in the Arundel Lyrics (Attributed to Peter of Blois)”

Mary Franklin-Brown, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Mary Franklin-Brown’s paper focused on a collection of poems found in one manuscript, the late fourteenth-century BL Arundel 384. [Catalogue record] It contains a collection of 16 love poems, datable to the 1170s or early 1180s. Franklin-Brown examined how a discourse on nature interacts with other discourses in the poetry (I’m so envious of people who can read Latin fluidly and elegantly!) and showed that the works contain multiple meanings, and both Ovidian and Neo-Platonic references.

“Beyond the Obvious: Aelfric and the Authority of Bede”

Joyce Hill, University of Leeds

Ælfric (c. 955-c.1010) was the first English author to work with imported Latin homilies in order to produce new texts in the vernacular. While drawing on Carolingian traditions, Ælfric also wrote from firmly within the reform movement of Anglo-Saxon Benedictine monasticism.

The main focus of Joyce Hill’s talk was Ælfric’s relationship with those texts on which he drew. She argued that the library which Ælfric had to hand must have been smaller than assumed by those scholars who have previously worked on his writings (Godden and Lapidge). For instance, she showed that Ælfric must have known Bede only through extracts from source homilaries.

This is not a period of history about which I know much, but regardless I appreciated the neat, clear way in which Prof. Hill laid out her methodology for working through the textual evidence in order to tease out the genealogy of the sources which Ælfric used.

[Image left: Cotton MS Claudius B IV f. 19r. Ælfric worked on part of this manuscript. Credit.]

And with that, the conference came to an end and we fled southwards in advance of the anticipated snowfall. Of course, this being the Midwest, the snow’s slowly followed us—the forecasted lows for tonight are already making me shiver and I haven’t even left the office yet.