This year’s Midwest Medieval History Conference was held at Dominican University, just outside of Chicago—what a lovely campus, and such a well-run event! My memories are a little fuzzy at this point, at a few days’ remove and with a lot of midterm exam grading in between, but here are my notes on the various panels.

Friday

Session 1—Medieval Cities

Chair: Linda E. Mitchell, University of Missouri–Kansas City

“Charity and the City: London Bridge, c. 1176-1265”

“Charity and the City: London Bridge, c. 1176-1265”

John McEwan, St. Louis University

The conference got underway with John McEwan’s exploration of the charitable corporation which grew up around the construction and maintenance of London Bridge. (A charity which still exists; that’s got to be some kind of record.) Dr McEwan argued that, contrary to the previous historiography, it was not inevitable that control of the bridge would be appropriated by the city government. It was perfectly successful and efficient on its own—which was precisely why it was taken over by the civic government, which was attracted by its financial and logistical potential.

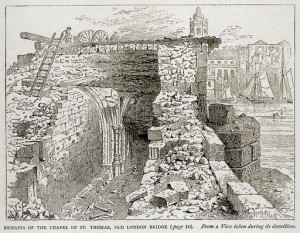

[Image to the above right shows the Chapel of St. Thomas at the time of its demolition. From Walter Thornbury, Old and new London, a narrative of its history, its people, and its places, vol. 2, pg. 12. (Archive.org)]

“Student Violence against Women at Oxford, 1200-1500”

Andrew E. Larsen, Marquette University

Andrew Larsen’s paper engaged with Ruth Mazo Karras’ recent work on medieval masculinity. He attempted to rebut her argument that, in part, students’ sense of their masculinity was constructed around violence against women. Through an examination of eyre court records and other documentary evidence, Prof. Larsen claimed that in fact student violence against women in late medieval Oxford was not common—this though Oxford in the fourteenth century was an extraordinarily violent place, with a murder rate some two to three times that of the much bigger London. He argued that this was—at least in part—because students were more likely to engage in illicit sexual activity with townswomen or prostitutes. This was one of the papers at the conference which sparked the most lively debate during the ensuing Q&A session.

“Caught between Town, Gown, and Crown: The Roles of the University in Freiburg”

Jason Ralph, Northwestern University

Jason Ralph’s paper examined a lawsuit which surely must be in contention for longest-running in the world. It began in 1489, between the town of Freiburg and its university, and continued until the 1700s. The dispute was mediated by the Hapsburg monarchy. Ralph argued, I think convincingly, that both town and university looked for the Hapsburgs’ intercession because each thought its case more convincing (the town claimed that the university having married members invalidated its claim to be a religious community and meant that it owed civic taxes), but that by doing so inadvertently strengthened the Hapsburgs’ control of the region.

Session 2—Medieval Women

Chair: Amy Livingstone, Wittenberg University

“Three Sisters: The Portuguese Monarchy, the Cistercian Order, and the Communities of Lorvão, Arouca and Celas”

“Three Sisters: The Portuguese Monarchy, the Cistercian Order, and the Communities of Lorvão, Arouca and Celas”

Miriam Shadis, Ohio University

Miriam Shadis’ paper looked at an area with whose history I’m not at all familiar—Portugal—but it provided another fascinating demonstration of the ways in which medieval religious women and their communities could exercise political power. The three Portuguese princesses Teresa, Sancha, and Mafalda, brought the first female Cistercian communities to the kingdom. They used these communities—and the lands which they owned—as part of their power struggle with their brother, Alfonso II. I thought that the map which Professor Shadis showed was very instructive. The sisters’ major foundations formed a line right down the centre of Portugal. Another instance of using female religious communities as a kind of soft power?

[Image left shows a 17th c. painting of Teresa, Sancha, and Mafalda of Portugal now held at the abbey of Lorvão. (Wikimedia Commons)]

“The Menagier de Paris: A Product of the Black Death”

Bobbi Sutherland, University of Dayton

Bobbi Sutherland’s paper took a text which is very well-known to medievalists—the Menagier de Paris, supposedly a late fourteenth-century guide to appropriate wifely behaviour—and re-examined the text’s purpose. Prof. Sutherland argued that there are some surprising omissions from a text that purports to teach a young woman how to be a wife (no childbirth? no weaving?) She proposed instead that it was intended as a collection of wisdom that the unknown author—who may well have lived through the Black Death—feared would be lost in a post-plague world.

Plenary Address

“Jean Gerson’s Musical Theory of the Emotions”

Barbara Rosenwein, Loyola University Chicago

The keynote speech was given by Barbara Rosenwein, who examined the writings of the French theologian Jean Gerson (1363-1429) in order to reconstruct his theory of emotions—a component of his writing which scholars have not previously recognised. Focusing primarily on his Tractatus de canticis and his Canticordum au pelerin, Prof. Rosenwein discussed Gerson’s idea of the silent music of the heart, something which, for the devout Christian who paid attention to it, was a means by which he or she could talk more easily with God. I know nothing about music, so I confess that some of the finer details of the hexachord and octaves and the Guidonian hand and how they were used by musicians in the medieval period went over my head. (I’m probably tone deaf, and only survived choir in secondary school by standing in the middle of a row and silently mouthing for most of it.) Even given that, however, I was still struck by the range and versatility of Gerson’s theory, which married singing with focused meditation on particular emotions. For someone to master this technique, they would have to be a true virtuoso indeed—I was really left wondering if anyone had ever managed it!

Saturday

Session 1—Pedagogy

Chair: Phillip C. Adamo, Augsburg College

“Fighting the Dragon: Making the Medieval Approachable for Children”

Michelle Morrison (Madison Children’s Museum and Schumacher Farm)

Michelle Morrison works at the Madison Children’s Museum, where there are clearly lot of wonderfully inventive programmes happening! She discussed the medieval fair programmes which the MCM runs as a way of teaching very young children about the Middle Ages through active, practical involvement—so for instance, having them build their own castles while asking them about the defensive choices they’re making, etc. These activities have the benefit of being low-risk learning—as Morrison said, “nobody flunks museums.” She also offered one of the best articulations I’ve heard recently of the ethical demands and pedagogical challenges of teaching, of ensuring that we convey our ideas and insights in a register appropriate to our audience.

“Weaving the Red Weft: Teaching Textiles in the Medieval Classroom”

“Weaving the Red Weft: Teaching Textiles in the Medieval Classroom”

Laura Michele Diener (Marshall University)

When was the last time you were asked to smell a bag of unprocessed Icelandic sheep’s wool at a conference? (Yes, it was quite odiferous.) This was definitely one of the most interactive papers of the conference, and I thought it was fabulous. As you can see from the picture to right (of my colleague, Kristi DiClemente), an audience volunteer was challenged to figure out how to use a spindle in the course of a panel, while Laura Michele Diener discussed how she uses these and other clothmaking and clothes-manufacturing techniques in the classroom to help her students appreciate both the nature of women’s work, the labour-intensive nature of production in an age before mass mechanisation, and the materiality of the Middle Ages. This made me want to learn how to weave and dye just so that I could do this in my own classroom!

“Playing the Middle Ages”

Louis Haas, Middle Tennessee State University

There was so much useful stuff in Prof. Haas’ presentation that I think it could easily have been a whole panel in and of itself. He shared a wide range of exercises which he has used in his classes over the years in order to engage students through performative and subversive play. Before the talk was even over I was already scribbling down ideas for ways in which I could adapt them for my own classes, and really appreciated Prof. Haas’ stress on the importance of the instructor giving up a little control in the classroom and being more facilitator than instructor.

Session 2—The Christian Life

Chair: Robert Lerner, Northwestern University

“Franciscan Poverty as Virtual Perfection: Peter Olivi’s Description of the Vita Apostolica in his Lectura super Matthaeum”

James M. Matenaer, Franciscan University

This paper delved into how Peter Olivi (1248-1298) used the Gospel of Matthew to support his views on the requirement of utter poverty for Franciscans. Olivi thought that the prefatory steps of entry into a religious order matched the stages by which the apostles began to follow Christ. These apostles, of course, were told famously not to worry about tomorrow, to sell everything they had if they wanted to be “perfect.” For Olivi, then, absolute poverty was the root of apostolic perfection, both the evidence of it and the material experience of it. It’s easy to see why Olivi was such a controversial figure, both in the Franciscan Order and in the wider church.

“Indulgences, Syon Abbey, and the Revelations of St. Bridget of Sweden”

Robert W. Shaffern, University of Scranton

Prof. Shaffern focused on one manuscript in particular, BL Harley 2321, the so-called Syon Pardon Sermon. Since it’s 55 folios in length, it’s really more of a treatise than a sermon; it’s likely that it’s a later expansion of an original sermon text. As Syon was a Birgittine community, it’s unsurprising that the text effectively harnessed the persuasive powers of St Brigit of Sweden’s mystical visions in Middle English translation in order to persuade the prospective reader (one of the community’s nuns?) that indulgences were a good and necessary thing.

Session 3—Crusades

Chair: Jonathan Lyon, University of Chicago

“‘Ignis de Caelo’: Natural Phenomena in the Chronicles of the First Crusade”

“‘Ignis de Caelo’: Natural Phenomena in the Chronicles of the First Crusade”

Elizabeth Lapina, University of Wisconsin-Madison

This was a great melding of science and history. Prof. Lapina discussed the description of a variety of natural phenomena in chronicles of the First Crusade—from comets to meteorites to aurorae to earthquake lights (a fascinating occurence that I’d not previously heard of; aren’t those photos in the linked article eerie?). Comets have received a lot of scholarly attention, whether it’s how one functions as an ill omen in the Bayeux Tapestry or as a miraculous portent in a nativity fresco by Giotto (shown left), but not so much other types of phenomena. Prof. Lapina discussed how the chroniclers’ mention of these things reflected their beliefs that they were truly living in the end times.

“Memory and the Crusades: Sermons as Vectors for Commemoration and Contextualization”

Jessalynn Bird, Independent Scholar

Dr Jessalynn Bird teased out the ways in which travelling preachers and writers such as Jacques de Vitry urged participation in the Crusades, both those to the Holy Land and those which took place in the south of France. In the latter instance in particular, Bird argues that we see the beginning of the idea of indulgences as something transferable, something you could earn but which you could then apply to a family member or loved one. After all, undertaking a crusade to Jerusalem was a costly affair that most people could only do once in a lifetime, but hunting out Cathars was something which theoretically could be undertaken several times by a French nobleman. If you’ve already racked up several thousand years worth of remission from Purgatory, why not try to share some of that with others?

“Muslim Communities’ Responses to the Renewed Frankish Rule of Jerusalem, 1229-1244”

Ann E. Zimo, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

The 1229 agreement with Frederick II, by which control of Jerusalem was returned to the Franks for a period of 10 years, is one which has been much studied by scholars in terms of the details of the treaty itself. Yet, Ann Zimo argued, almost no work has been done on the representation of the handover in the Arabic sources, or on the history of the Muslims who remained in the city during this period. For Muslim commentators, it seems, Frankish rule was less of an issue than was the Muslim princes giving up the city in the first place. Zimo teased out both their responses, and the ways in which Muslim religious life continued in Jerusalem.

“Narrating Ceremony and Celebration among the Franks in the Latin East, 1221-1286”

Jesse W. Izzo, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Jesse Izzo examined the “Chronicle of the Templar of Tyre” as a literary and cultural production, a mode of analysis which he argued has not been used much for sources from the Latin East. He discussed various instances from the Chronicle—jousts between knights dressed as nuns or Arthurian heroes, amongst other guises—as a form of role-playing which both flattered noble vanities and allowed for the ritual settling of differences. Izzo argued that this was an early instance of gestures of symbolic communication and consensus which wouldn’t appear in the Latin West until the fourteenth or fifteenth centuries.

Session 4—Medieval Law

Chair: Richard Helmholz, University of Chicago

“Aprisio Revisited: The Roles of Carolingian Kings in Local Arrangements”

Cullen Chandler, Lycoming College

Leading off the final session was Prof. Cullen Chandler, who was presenting another installment of an ongoing debate between himself and Jonathan Jarrett about aprisio, a kind of land settlement procedure used in Carolingian Catalonia. (An overview of the various stages of the debate can be seen here at Jarrett’s blog, and here at Chandler’s blog.) To simplify the subject of the debate, Chandler believes that aprisio was a means for Charlemagne to extend his royal authority in the region; Jarrett believes that it was a purely local phenomenon which had little to nothing to do with the monarchy. This is way out of my area of expertise, so I’m not going to presume to come down on either side. However, I will say that I was very impressed throughout the paper by the good-natured way in which Prof. Chandler engaged in debate. He clearly thinks Dr Jarrett is wrong, but his respect for him as a scholar was still clear—I thought it was a model for future papers in this mode.

“‘I do… Not!’: Coerced Marriages in a Medieval French Court”

Kristi DiClemente, University of Iowa

My colleague Kristi DiClemente discussed part of the findings of her doctoral research. She works on marital disputes in late medieval Paris, and in this paper was focusing on a particular set of cases—marriages conducted per verba de futuro, which hadn’t been consummated, where the man brought the woman to the court claiming that they were married, but which the woman denied. Kristi here focused on the ways in which the court records shows these women as “performing” their refusal of the marriage. She argued that the women were following cultural scripts in order to make a successful case, something which hints at a pool of legal knowledge shared by and among laywomen.

[Image above right, BL Additional 24678, f. 22]

“‘Beloved and Faithful’: Expressing Loyalty in French Legal Culture”

Jolanta N. Komornicka, University of Virginia

The last paper of the conference was given by Prof. Jolanta Komornicka, who presented an extremely interesting look at the role of emotions in legal cases in thirteenth and fourteenth-century northern France. ‘Love’ and ‘loyalty’ are words which appear with great frequency in the records of a system which was increasingly interested in issues of treason and disloyalty. Justices and magistrates as well as litigants expressed these emotions during court cases—this emotional lexicon, in other words, was both aspirational and affirmational, marking out those royal officials who did well and those who did not.