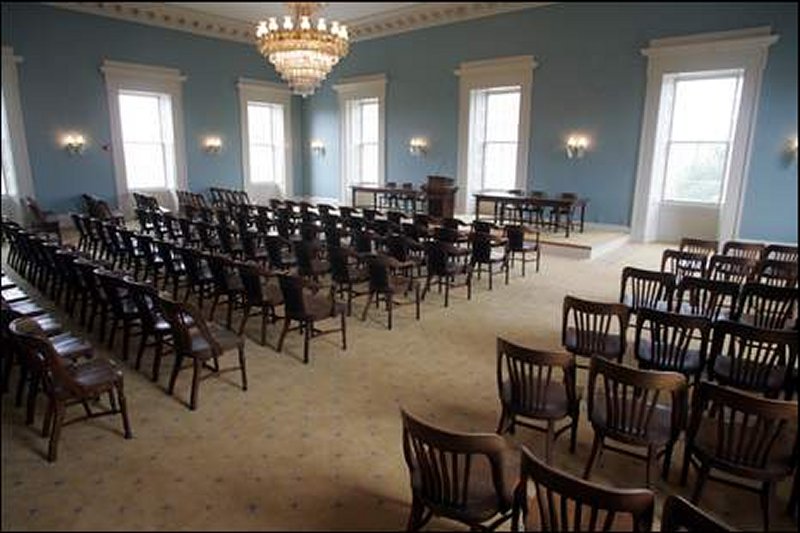

For the past two days, the Old Capitol here has been host to A World of Citizens: Women, History, and the Vision of Linda K. Kerber: a symposium in honour of Professor Linda Kerber, who has retired this year from the University of Iowa’s Department of History.

While my areas of research are very different from those of Professor Kerber—her work looks at women in the nineteenth and twentieth United States, with a special focus on the history of citizenship, gender, and authority—I think there are few scholars working on women’s history who haven’t been influenced by Kerber’s scholarship in some way, however indirect. At the very least, she was part of that pioneering generation which helped to make women’s history a part of university curricula. It was fascinating then, for this medievalist, to get to attend a part of the symposium, and to hear about the work of what one of the participants called “the Kerber diaspora”—to get a sense of the ways in which so many historical subdisciplines have been changed by the new questions which women’s historians have asked over the past few decades.

You can see the full symposium program here; my notes about the sessions which I was able to attend today are below.

SESSION 1. “Families and Citizenship” — Sheila Skemp, University of Mississippi (Chair)

Catherine Denial (Knox College) started the day’s sessions with her paper on marriage in Dakota Country from 1835-45. Denial argued that marriage was used both as a tool of nation-building by American settlers moving into the region, and as a means of resistance by the Dakota, the Ojibwe and the mixed-heritage individuals who already lived there. Christian missionaries sought wives who would help them to live in a “civilised” manner, and their wives tried to “educate” Dakota and Ojibwe women about more appropriate gender and marital roles. By refusing to adopt Euro-American marriage customs, or by creating hybrid customs, Dakota and Ojibwe people were able to push back against the burgeoning American state.

Judy Nolte Temple (University of Arizona) shared some of her research into a variety of 19th and 20th century white American women’s diaries, using them as a lens through which to examine how women thought of citizenship. Women like Emily Hawley Gillespie (pictured right) and Elizabeth McCourt were American, but not fully citizens according to the laws of their day, while Mary Eileen Murphy Welsh was an Irish immigrant whose diary recorded her complicated feelings about belonging in her new Arizonan home.

Judy Nolte Temple (University of Arizona) shared some of her research into a variety of 19th and 20th century white American women’s diaries, using them as a lens through which to examine how women thought of citizenship. Women like Emily Hawley Gillespie (pictured right) and Elizabeth McCourt were American, but not fully citizens according to the laws of their day, while Mary Eileen Murphy Welsh was an Irish immigrant whose diary recorded her complicated feelings about belonging in her new Arizonan home.

Michael Innis-Jiménez (University of Alabama) then spoke about the experiences of Mexican immigrants in interwar Chicago, and how they were cast as “sojourners”—bound together by their shared origins and their hopes of a new life, but held back from full integration by white Chicagoan hostility and a Mexican political narrative that assumed an ultimate return on their part to Mexico. Lastly, Eryn Kane (Ohio University) shared some of her research for her Master’s thesis, on how the ideology of republican motherhood was used to reinforce gender roles after the destablising effects of World War II.

SESSION 2. “Citizenship, Activism, and Political Commitment” — Cornelia Hughes Dayton, University of Connecticut (Chair)

The first paper was by Elizabeth Israels Perry (Saint Louis University), who unfortunately couldn’t attend due to illness. Her paper was instead delivered—with much verve! a hallmark of much of this session—by Mary Kelley (University of Michigan). In it, Perry outlined her plans for a future book, one on women in New York City in the post-suffrage era, which would push back against the traditional narrative about politics of the period. That has cast the time primarily in terms of the struggles of (male) Tammany Hall Democrats, and the supposed failure of women to achieve much by way of political involvement; Perry would argue to the contrary, and aims to write a group biography of those whom she calls “LaGuardia’s Women”, appointed to various positions by New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia.

Alison Kibler (Franklin and Marshall College) discussed the context of a 1976 petition by a group called the Feminists for Media Rights to deny a broadcast licence to a station in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. FMR’s petition was based on a perceived failure on the station’s part to produce enough programming for, or to provide sufficient employment for, women. FMR technically lost their case, but succeeded in winning concessions from the station’s management in a manner which Kibler contrasted with the methodology of early 20th century activists—what she termed a novel way of allowing for group advocacy amid the flourishing of free market ideals.

Karissa Haugeberg (Tulane University), a very recent PhD from the University of Iowa, gave a really fascinating paper on attitudes held by nurses towards women seeking abortions from 1967 (after elective abortions were legalised in Colorado) to 1973 (Roe vs. Wade). Haugeberg argued that even though many nurses had assisted during abortion procedures before legalisation, their attitudes shifted against the women undergoing the procedure because of a variety of reasons—lack of preparation, lack of interaction with the patients, a shift from hospital-based approval procedures to one based solely on a woman’s right to choose. Haugeberg also placed these tensions against a backdrop of a nursing profession that was being transformed at this time, with nurses protesting gendered stereotypes.

Lastly, Jane Simonsen (Augustana College) looked at how citizenship is constructed, analysed and understood in a variety of intersecting places in Rock Island, Illinois: in her classroom at Augustana College; at the Blackhawk State Historical Site, where the early 19th century war between the Sauk nation and American colonists is remembered in very different ways by white Americans and by the Sauk people; and in a 1921 play, Inheritors, by Quad Cities native Susan Glaspell. I thought that Simonsen opened up some really fascinating avenues of inquiry with her paper, particularly as to how citizenship (as something gendered and racialised, as something which requires dissent) can be dissected in the classroom, and I look forward to reading the finished piece.

Lastly, Jane Simonsen (Augustana College) looked at how citizenship is constructed, analysed and understood in a variety of intersecting places in Rock Island, Illinois: in her classroom at Augustana College; at the Blackhawk State Historical Site, where the early 19th century war between the Sauk nation and American colonists is remembered in very different ways by white Americans and by the Sauk people; and in a 1921 play, Inheritors, by Quad Cities native Susan Glaspell. I thought that Simonsen opened up some really fascinating avenues of inquiry with her paper, particularly as to how citizenship (as something gendered and racialised, as something which requires dissent) can be dissected in the classroom, and I look forward to reading the finished piece.

SESSION 3. “International Dimensions of Citizenship” — Sharon Halevi, University of Haifa (Chair)

Megan Threlkeld (Denison University) looked at how a group of American female activists conceived of the “world citizen” in the early twentieth century. She contrasted those who thought of it in what she thought the “advanced kindergarten” mode (mandating increased respect, sharing knowledge and working towards peace through education) with those who desired a world-wide federation of nations. In both, there was a sense of the USA being both a model and a world leader in these endeavours.

Michaela Hoenicke-Moore (University of Iowa) looked at the cases of three German-American women—Margret Boveri (pictured right), Toni Sender and Charlotte Beradt—who had fraught relationships with their own citizenships thanks to the political climate of Germany in the 30s and 40s, thanks to their own religious and political identities (Judaism, socialism, ultra-nationalism), and their emigration to the United States.

Michaela Hoenicke-Moore (University of Iowa) looked at the cases of three German-American women—Margret Boveri (pictured right), Toni Sender and Charlotte Beradt—who had fraught relationships with their own citizenships thanks to the political climate of Germany in the 30s and 40s, thanks to their own religious and political identities (Judaism, socialism, ultra-nationalism), and their emigration to the United States.

Caroline Campbell (University of North Dakota) brought us back to Europe, with a look at French women who belonged to ultra-national groups during the French Third Republic—a salutary reminder that just as women can work for progressive causes, so too can they work for highly conservative or reactionary ones. Campbell pointed out that while scholars have presumed that French right wing groups in the 30s were not as violent as those elsewhere in Europe, this is because too limited a construct of “violence” has been used—and in fact, that “provocative violence” or “emotional violence” could be just as devastating as physical violence for its victims. Eileen Boris (University of California at Santa Barbara), lastly, looked at the conflicts between groups like the International Labor Organisation and the United Nations over labour equality—should class equality or gender equality come first, the debate ran?

Sadly, after this I had to leave, but it was nice to get to experience a different facet of the profession than I normally get to experience, to see how fellow scholars grapple with concepts—like citizenship or transnational movements—which are not readily employed by medievalists, and of course to see the kinds of scholarly networks which can be created by determined and focused academics like Professor Kerber.