This post first appeared in Les Enluminures’ TextManuscripts blog.

The first time that one of my students had the opportunity to pick up a fifteenth-century breviary, he was so nervous he could hardly bring himself to touch it; another pair of students in the same class were so excited at the prospect of leafing through a late medieval Book of Hours that they couldn’t stop giggling. Students exclaimed in delight over the size of a thirteenth-century Parisian Bible—one small enough to fit into the palm of your hand—and experimented to see if they could truly feel the grain of the parchment with their fingertips. Some even dared to sniff at the manuscripts’ bindings, to see what something centuries old might smell like.

(The most perplexing conclusion? Like barbecue-flavor chips.)

As wonderful as digitized manuscripts are, and as great a tool as they can be for researchers or in the classroom, there is nothing like getting to sit with a manuscript in person and to turn its pages: to not simply read texts in translation from the Middle Ages, or to look at photos of illuminated manuscripts, but to be historians in a very hands-on way.

Through SUNY Geneseo’s participation in the Manuscripts in the Curriculum program in the Fall 2021 Semester, our students were able to work directly with nine different medieval manuscripts. This was a brand new experience for them as Geneseo’s Special Collections holds only two individual medieval manuscript leaves, and no full manuscript volumes from the Middle Ages: this is not an experience our students could have had without participation in this program.

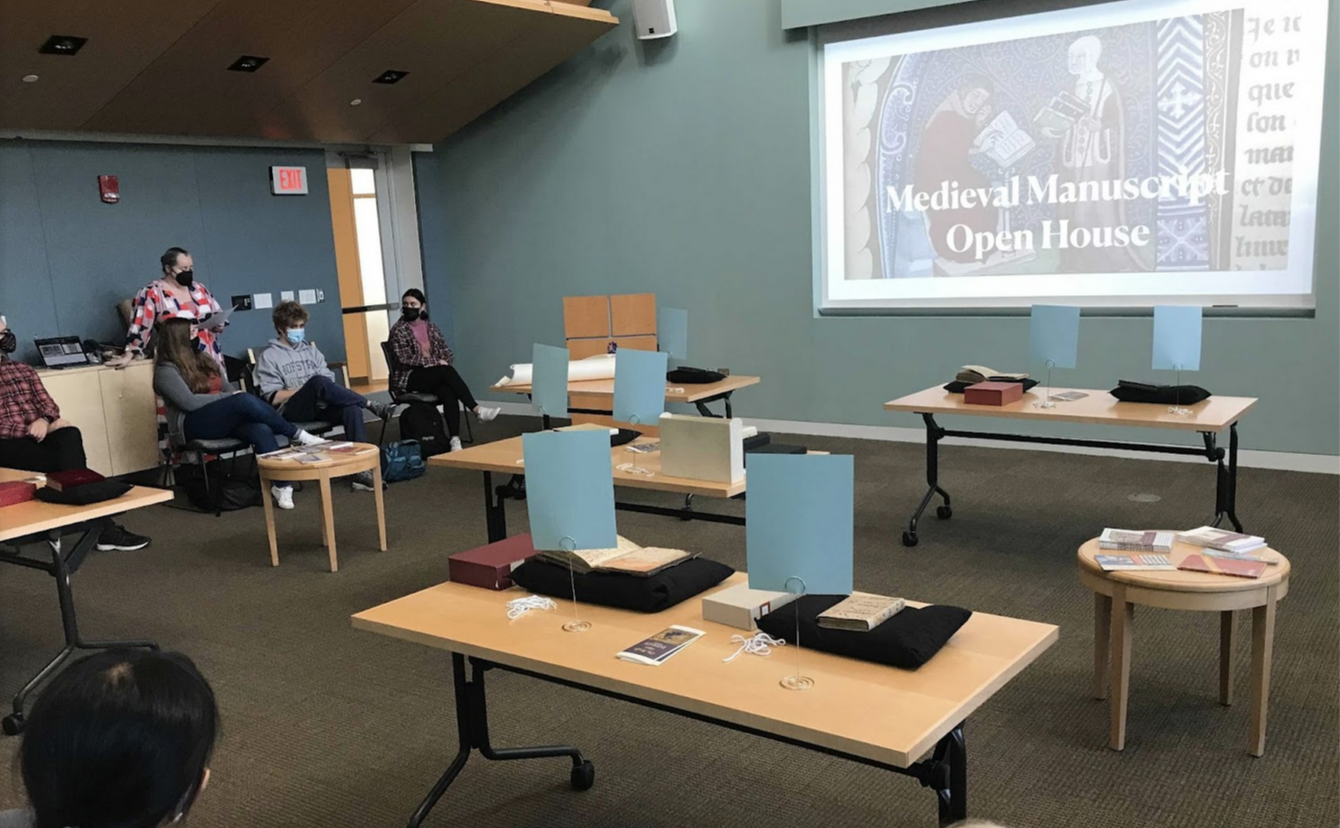

Students in Professor Beverly Evans’ “Medieval and Renaissance French Literature” course explore the manuscripts, in the company of Special Collections Archivist Elizabeth Argentieri (photo by Beverly Evans).

Students in Professor Beverly Evans’ “Medieval and Renaissance French Literature” course explore the manuscripts, in the company of Special Collections Archivist Elizabeth Argentieri (photo by Beverly Evans).

Students taking courses from across our Medieval Studies offerings—from Medieval and Renaissance Literature to Elementary Latin—had the opportunity to explore the manuscripts one-on-one.

However, I also crafted two new History courses around the manuscripts that let students work with them in-depth: the introductory-level “The History of the Book in Medieval Europe” and the upper-level “The Book and Book Cultures in Medieval Europe.” Both courses aimed to get students to think actively and expansively about the book as a vital technology in the Middle Ages. They studied quires and collations and bindings, practiced writing themselves with quill pens and ink (they discovered that their hands quickly ached and that a quill pen works very differently to a ballpoint one!), and learned a little about how to read a Gothic bookhand.

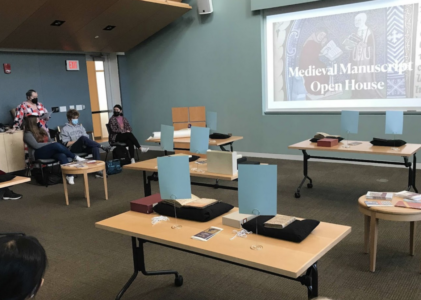

Some of the manuscripts on display in Fraser Library, SUNY Geneseo. The descriptive labels were written in collaboration with students in my courses (photo by Yvonne Seale).

Some of the manuscripts on display in Fraser Library, SUNY Geneseo. The descriptive labels were written in collaboration with students in my courses (photo by Yvonne Seale).

The students in these book history courses also learned how to communicate their new-found knowledge to others. Students in the upper-level course, for instance, contributed to the research and writing of the labels which accompanied the public display of the manuscripts which Fraser Library staff created. The most prominent example of this, however, occurred in December, when the students in my introductory-level course hosted approximately thirty middle- and high-school social studies students from Geneseo Central School District.

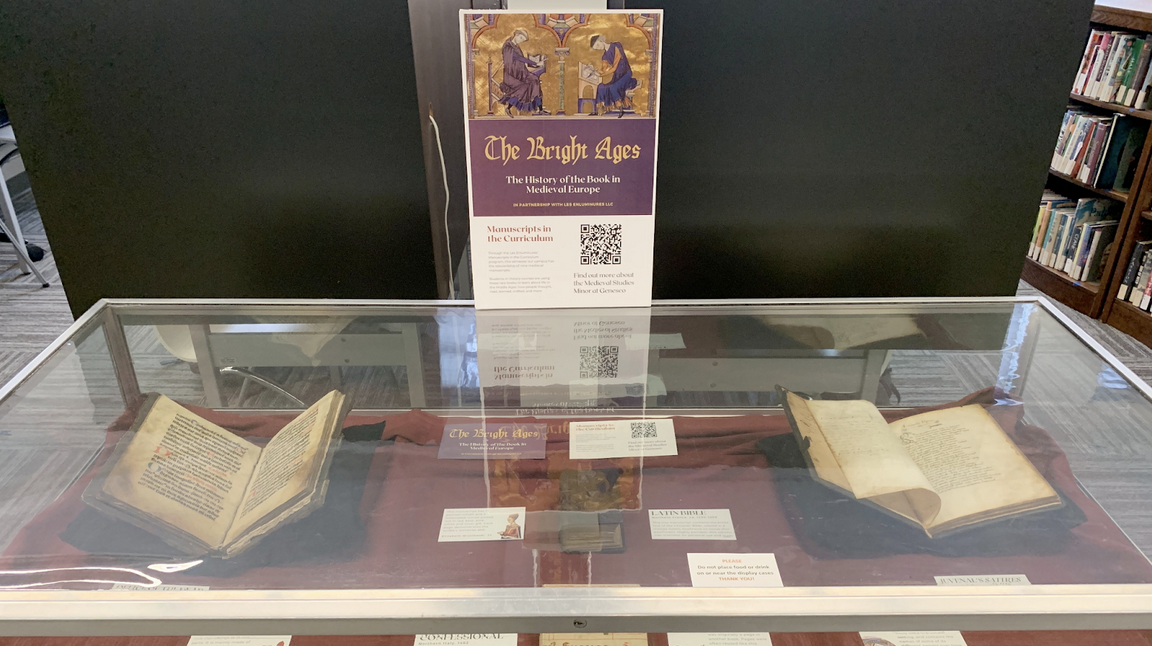

Students from my “The History of the Book in Medieval Europe” course explain the historical significance of a thirteenth-century Parisian Bible to a group of students from Geneseo Central School (photo by Yvonne Seale).

Students from my “The History of the Book in Medieval Europe” course explain the historical significance of a thirteenth-century Parisian Bible to a group of students from Geneseo Central School (photo by Yvonne Seale).

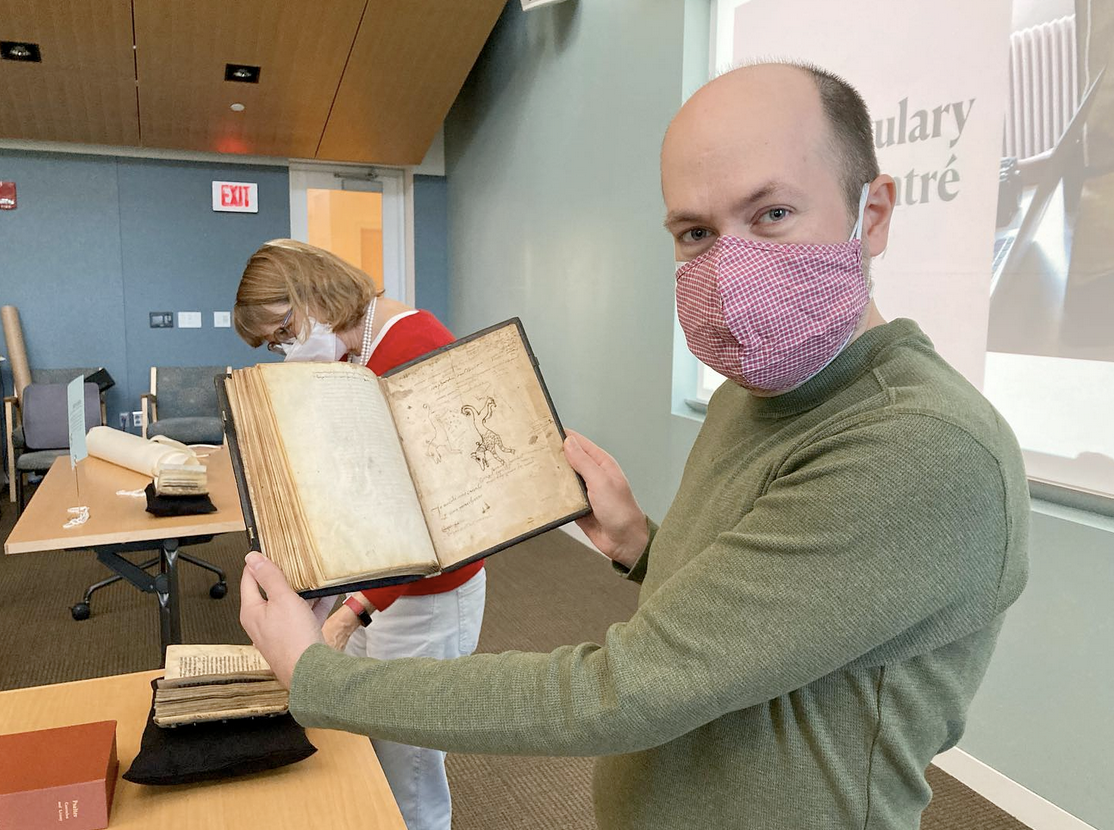

My students had previously been divided up into groups of three or four and had “adopted” a manuscript to work with. Their task had been to research that manuscript’s history and composition, together with the history of its genre, and to come up with a brief presentation to make to the visiting students which conveyed to them what this volume could tell us about the history of the book and of medieval Europe more broadly. This vibrant event set the college ballroom buzzing as the visiting students circulated from table to table and their older counterparts dove into the challenge of being active teachers in their own right. The marginalia, pen trials, and other doodles were a big hit! History/Education majors in particular relished the opportunity to marry the skills acquired in both parts of their major.

History Professor Ryan Jones showing one of the doodles that was a particular hit with staff and students (photo by Yvonne Seale).

History Professor Ryan Jones showing one of the doodles that was a particular hit with staff and students (photo by Yvonne Seale).

Many of the students who signed up for my upper-level course on book history wrote in their end-of-semester reflection that they had initially been skeptical about the entire concept of a semester-long course on the history of the book. A book is just a book: what more is there to say about it? What could possibly be interesting about studying how books are made? Wasn’t this just an odd way of saying that they’d be reading books in the course?

Students from my “The History of the Book in Medieval Europe” course sharing their knowledge with groups of students from Geneseo Central School.

Students from my “The History of the Book in Medieval Europe” course sharing their knowledge with groups of students from Geneseo Central School.

Yet as the semester progressed, the students’ perspectives shifted. We looked at books from perspectives that they hadn’t considered before: faith, gender, colonialism, and more. We discussed exactly what it is that historians do when they research, and the expertise of archivists and conservationists. We revisited the manuscripts again and again, looking at them from new angles (both literal and metaphorical) each time, as our knowledge grew and our conversations deepened. Examinations of marginalia and colophons helped to spark classroom exchanges about love letters and notes from loved ones. More than one student reported having phoned home to share what they had learned and to ask questions that had never occurred to them before about family Bibles or Haggadot, and what they meant to their parents and grandparents. This was deeply meaningful to my students and to me.

A book is not just a book, but a whole community—of knowledge, of experiences, of interconnections—given form in parchment or paper. We at Geneseo are very grateful to Les Enluminures for allowing us the opportunity to build a new community of the book here on our campus.