Very few medieval buildings have survived the centuries without major changes, and the former church of St Mary’s in Kilkenny is not one of them. Over the years, it has lost and regained a steeple, a chancel, and sheer square footage; its roof dates mostly from the early modern period; its medieval frescoes are almost entirely gone and chunks of its plaster ceiling are missing. Though still hemmed in by the close formed by the houses of Kilkenny’s prosperous medieval merchants, St Mary’s now feels a little removed from the contemporary bustle of the city’s High Street. The building’s long and complicated architectural history makes it the ideal home for what is, I think, the country’s newest museum: the Medieval Mile Museum (MMM).

I had a quick look around the MMM yesterday, and while the space is still settling a little into its new identity as a museum, it’s already a wonderful addition to Ireland’s cultural landscape. The architects and conservationists who collaborated on St Mary’s transformation into the MMM clearly thought long and hard about how to balance the abstraction of a museum with the physicality of a medieval structure with a varied history.

From the exterior, the building’s original ecclesiastical function is clear. St Mary’s was founded as Kilkenny’s parish church at some point in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century—certainly by 1205—by William Marshal, lord of Leinster. Marshal is a figure well-known to medieval historians, a powerful Anglo-Norman soldier and statesman who also built the first stone castle in Kilkenny. (It lies just a short walk from the MMM). The church’s size and grandeur, and the impressive tombs which still surround it, are testament to the civic pride and mercantile success of Kilkenny’s medieval burgesses.

But step inside and you’re in a place whose purpose is civic pride of a different kind: to gather and showcase the highlights of the medieval and early modern material heritage of Kilkenny City and its surrounding county. Right now, tomb slabs, effigies, and some replica high crosses predominate, though more artefacts are apparently due to join them this coming autumn. The interior’s bright white walls set off the items on display as effectively as any purpose-designed gallery. Glass inserts in the floor provide glimpses of crypts and the original medieval floor level; a great section has been cut out of the ceiling plaster over the crossing, letting you look up into the roof’s timber beams.

A lot of thought clearly went into considering light and making sure that sight-lines are uncluttered. I visited on that rare feature of an Irish summer, a sunny day, but it’s hard to imagine the MMM feeling gloomy even in the depths of winter. Pretty much every direction you look creates interesting juxtapositions between artefacts, and thoughtfully placed benches encourage you to sit and take advantage of that. This is one of the aspects of the museum which will surely make it attractive to visiting school groups.

The building’s original footprint has also been restored thanks to a new extension made of wood and lead. The extension’s simple lines and muted colours complement the existing structure while recreating the volume and visual density of the lost medieval chancel (which was mostly dismantled during the eighteenth century). From the exterior, the two parts of the building look seamless; yet from the interior, it’s clear that the extension floats over the remains of the chancel walls and the tombs below. There’s something quite arresting about seeing something so massive be made to seem so weightless.

This new chancel houses some of the city’s medieval and early modern manuscript treasures, including pieces of civil legislation (concerning, for example, how to punish “bawdy hoores and cnaves”), various royal charters and the priceless Liber primus Kilkenniensis. Another large window here lets you look out over the rooftops of Kilkenny and try to imagine how much of the skyline would be at all familiar to the people who wrote the texts which surround you.

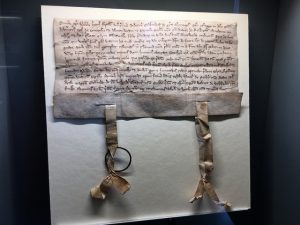

I would have liked if the room provided a little more contextualisation of the individual documents and of the circumstances and settings under which they were produced, but that’s perhaps the inevitable lament of the medieval history nerd about something which is aimed at the general public. (Give me more about the institutional relationship between the bishopric and the town!) Still, there are some little gems to discover, like the thirteenth-century charter issued by a bishop of Ossory which let friars in Kilkenny tap into his water supply—but the pipe they used couldn’t exceed a certain diameter. Helpfully, as you can see below, he attached a metal ring to the charter specifying the exact size.

Working with the history of St Mary’s, its original structure and later interventions, was a very sensible idea on the part of those involved in the MMM’s creation. It gestures generously to the past, but is confident in its developing identity as a modern institution. The new museum is sure to become a fixture for those who research and teach the Middle Ages.