This was a conference of firsts—my first time in Stirling, and my first time to leave Scotland with a tan (or at least as much of a tan as someone of my usual pallor can achieve)! The heat was certainly a lot to take. While highs of 27 or 28C might be comparatively cool in an Iowan summer, Scottish architecture just isn’t equipped to cope with temperatures like that. I’ve never seen so many conference programmes employed as makeshift fans! That said, both the city of Stirling and the university campus were beautiful, and showed to their best in the sunshine, and I had a lovely time.

My camera’s batteries decided to die just before the trip to Dunblane Cathedral, but I had remedied that by the time of my Friday jaunt around Stirling town centre and the nearby ruins of the abbey of Cambuskenneth. I’ve uploaded my photos here at my Flickr account.

“The Start of It All: Selkirk/Kelso and Reformed Monasticism in Scotland.” — Richard Oram (University of Stirling)

Prof. Oram’s introductory lecture was a passionate argument in favour of further study of monasticism in Scotland, particularly study which was aimed at a popular audience and which could function as a corrective against the idea of the Celtic churches as somewhat isolated from the continent and almost proto-Presbyterian.

Oram discussed the arrival of the Tironensian Order—which was French in origin—at Selkirk in 1113 and their subsequent removal to Kelso (pictured right) in 1128, and argued that they have been understudied because, unlike the Cistercians, the Scottish Tironensians lacked a chronicle-writing tradition. Certainly the vast incomes of their houses demand further investigation of their socio-economic impact, if nothing else. Kelso was located in the commercial heartland of the Scottish kingdom, while on its dissolution in 1561, the Tironensian abbey at Arbroath had an income of some £10,970 and boasted a relic of Thomas Becket.

PANEL 1 — MONKS, NUNS AND CANONS IN NORTHERN EUROPE I: AUGUSTINIANS, BENEDICTINES, AND CISTERCIANS

Øystein Ekroll (Norwegian University of Science and Technology) spoke on the Augustinian Order in Norway. Monasticism never gained a strong foothold in medieval Norway—there were perhaps 30 to 35 institutions in the whole kingdom—and they are little studied. Ekroll provided a brief overview of all of these houses, but his focus was on the Augustinian canons. He argued that their houses were some of the best documented because of the political dominance of one of their number, Eystein Erlendsson, second archbishop of Nidaros and the prelate who had crowned King Magnus in 1163 in the first coronation to occur in Scandinavia.

Emilia Jamroziak (University of Leeds) looked at the role of Cistercian houses in northern and northeastern Europe between the 12th and the 15th centuries. Prof. Jamroziak’s talk was similar in inspiration to her most recent monograph, Survival and Success on Medieval Borders, discussing the reasons for Cistercian expansion into particular areas, and arguing for regionalisation and fragmentation as a Cistercian characteristic. She rightly emphasised that no one area can be seen as providing the defining norm of the Order.

Izzy Hampton (University of York) discussed the powerful Neville family’s patronage of Durham Cathedral from the mid 14th century onwards, with a particular focus on the artistic objects which they donated. She argued that the proliferation of items associated with the Nevilles in the cathedral reflected their rise to social and political prominence. Some of their offerings—such as the finely embroidered priests’ vestments—have sadly long since disappeared, while some of their funeral effigies have been displaced or badly damaged; others, like the finely carved rood screen (pictured left), survive largely intact. I was particularly charmed by the fact that the screen’s local and dynastic connections were signalled not just by the inclusion of the Neville’s family crest, but by carvings of a breed of duck found in the area which is particularly associated with St Cuthbert. (The BBC has a nice article here about St Cuthbert and the Farne Island eider duck, if you want to read some more about them.)

Izzy Hampton (University of York) discussed the powerful Neville family’s patronage of Durham Cathedral from the mid 14th century onwards, with a particular focus on the artistic objects which they donated. She argued that the proliferation of items associated with the Nevilles in the cathedral reflected their rise to social and political prominence. Some of their offerings—such as the finely embroidered priests’ vestments—have sadly long since disappeared, while some of their funeral effigies have been displaced or badly damaged; others, like the finely carved rood screen (pictured left), survive largely intact. I was particularly charmed by the fact that the screen’s local and dynastic connections were signalled not just by the inclusion of the Neville’s family crest, but by carvings of a breed of duck found in the area which is particularly associated with St Cuthbert. (The BBC has a nice article here about St Cuthbert and the Farne Island eider duck, if you want to read some more about them.)

PLENARY 1

Constance Berman (University of Iowa) – “Amelioration and Investment by Cistercian Monks and Nuns.”

The focus and thrust of Connie’s plenary talk will, I’m sure, come as no surprise to those who are familiar with her work. Through an examination of the amelioration work carried out on their properties by Cistercian communities—such as forestry or establishing water mills—she explored what she called the Cistercian “diversity of accommodation,” and argued for such work being less independent of secular development trends than previously thought.

PANEL 6 – MONASTIC LIFE: THE CLOISTER AND THE WORLD BEYOND

Mark Hall (Perth Museum and Art Gallery) provided an interesting overview of some of the material evidence for play in a reformed monastic context. While the Bible links play with idolatry and idleness, it’s also linked with wisdom. Indeed, Thomas Aquinas endorsed the usefulness of play in his Summa Theologica. Mr. Hall showed us a wonderful range of archaeological finds such as dice and gaming boards which were used to play everything from chess to daldos, fox and geese/alquerque, and nine men’s morris.

Lene Myrdal (University of Bergen) examined the documentary evidence for medieval religious houses in the diocese of Oslo, which contained 12 of the kingdom’s 30 monasteries. There’s little surviving documentation—something which scholars of medieval Irish monasticism would be familiar with—but Ms. Myrdal was able to tease out some interesting implications nonetheless. For instance, the monastery of St Olaf at Tønsberg shows up most frequently in the records as a meeting place for resolving conflicts, telling us something about the social roles of medieval Norwegian religious houses.

Julie Kerr (University of St Andrews) then looked at monastic hospitality, and how different orders offered hospitality to other orders or to lay people in different ways. The Carthusians, for instance, feared that offering hospitality was the first step on the slippery slope to mendicancy, whereas extending a warm welcome to guests was instrinsic to Cistercian self-identity.

PANEL 8 – TRADITION AND REFORM IN THE ANGLO-SCOTTISH BORDERLANDS

Neil McGuigan‘s (University of St Andrews) paper looked at the church in Lothian and Teviotdale before the Scoto-Norman period, so in the 10th and 11th centuries. He used evidence of ecclesiastical boundaries and place names to estimate the southerly extent of Scottish royal power in the period.

Richard Oram (University of Stirling) provided an overview of the Premonstratensian order in Scotland. The order’s six houses in the kingdom were primarily patronised by magnate families, rather than by the royal family, and were mostly located on Scotland’s peripheries, in areas that were politically and culturally borderlands. I found particularly interesting his discussion of Dryburgh, a foundation the ambitions of which always seem to have exceeded its financial resources. In an attempt to avoid a sort of monastic bankruptcy, its monks offered cut price admission to its obit book, requiem masses and so on, meaning that Dryburgh’s records record the names of the kind of middling families who tend otherwise noto to appear in the sources.

Lastly in this session, Judith Frost (University of York) used a case study of the monastery at Guisborough to examine the strategies used by independent houses of Augustinian houses to navigate times of trouble. Guisborough and many other houses established confraternities which replicated the support networks used by more formally arranged religious orders. Guisborough’s confraternity list survives—I believe in its psalter (an illumination of which is pictured right), though I may have misheard that. What I found really interesting was the way Dr. Frost was able to compare and contrast Guisborough’s networks with those established by other Augustinian houses—there’s something potentially very interesting in examining this medieval monastic “social networking” which could tell us a lot about how these houses saw themselves. For example, while some houses had reciprocal agreements with their peers on the Continent, Guisborough’s were all British and mostly located in the north and east of England, stretching up towards Scotland.

Lastly in this session, Judith Frost (University of York) used a case study of the monastery at Guisborough to examine the strategies used by independent houses of Augustinian houses to navigate times of trouble. Guisborough and many other houses established confraternities which replicated the support networks used by more formally arranged religious orders. Guisborough’s confraternity list survives—I believe in its psalter (an illumination of which is pictured right), though I may have misheard that. What I found really interesting was the way Dr. Frost was able to compare and contrast Guisborough’s networks with those established by other Augustinian houses—there’s something potentially very interesting in examining this medieval monastic “social networking” which could tell us a lot about how these houses saw themselves. For example, while some houses had reciprocal agreements with their peers on the Continent, Guisborough’s were all British and mostly located in the north and east of England, stretching up towards Scotland.

PLENARY 2

Janet Burton (University of Wales Trinity Saint David) – “The Regular Canons in Britain: Transition and Transformation, Reappraisal—and Rehabilitation?”

The conference’s second plenary lecture focused on the more than 200 houses of regular canons which once existed in Britain—far more than the Cistercians, but far less studied. Prof. Burton summarised some of the scholarship on the canons, and rejected the conclusions of some eminent historians such as R.W. Southern (who saw the canons as successful because they were moderate and capable of living within modest means) or Dom David Knowles (who thought that their “continued existence served no good purpose whatsoever” because by the 15th century they were “the least fervent, the worst disciplined and the most decayed of all the religious houses.”) Instead, Prof. Burton sees houses which were often physically prominent on the landscape, promoted by leading churchmen, and both economically and spiritually important.

PRESENTATION – 3-D VISUALISATION OF ST ANDREWS CATHEDRAL PRIORY

Allan Millar and Richard Fawcett (University of St Andrews)

Despite my interest in the digital humanities, I know far less about the coding/computer science side of things than I should. For this reason, while I didn’t understand much about the technical side of this, I found the presentation very interesting. It’s still a work in progress—I believe they are using a platform called OpenSimulator—but given the scope to add in some very fine detail, it looks as if it will have great potential. For example, the program can run historical weather patterns to tell you what the light in the cathedral would have been at 7am on March 3, 1468.

PANEL 10 – SOURCES AND HISTORY: PROPERTY AND IDENTITY

Richard Millar (University of Stirling) examined the two surviving monastic cartularies of Scone Abbey. The two cartularies are closely related—the fifteenth century one is a partial copy of the fourteenth century one—but there are substantial differences. The fifteenth century cartulary contains a foundation charter and other early royal charters which are missing from the fourteenth century version; Mr Millar believes that these charters were “reconstructed” from later confirmation charters.

Brian Golding (University of Southampton) looked at the foundation accounts of Stone Priory and Dale Abbey, seeing in the construction of these narratives a way for these two institutions to assert their independence. In particular, he argues that as Stone Priory lacked a powerful patron, it constructed a story about its ancient, Anglo-Saxon origins in order both to attract pilgrims and to assert its independence from Kenilworth.

PANEL 11 – FEMALE RELIGIOUS HOUSES IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND

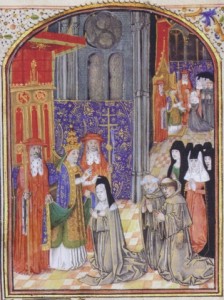

Anna Campbell (University of Reading) focused on the life of St Colette of Corbie (pictured left), a truly formidable woman who devoted her life to reforming the Franciscans and Clarissans. In her lifetime she refounded seventeen houses, mostly in Burgundy but also some in what is now northern France. Dr. Campbell focused on two case studies—that of Poligny and Amiens—to examine cases in which Colette’s desire for absolute poverty caused social and economic conflict. I found this such a strong, succinct reminder of the fact that the foundation of a monastic community could have profound consequences for the wider secular community—a mendicant may decide to give up all their property, but that doesn’t make the need for basic necessities go away.

Anna Campbell (University of Reading) focused on the life of St Colette of Corbie (pictured left), a truly formidable woman who devoted her life to reforming the Franciscans and Clarissans. In her lifetime she refounded seventeen houses, mostly in Burgundy but also some in what is now northern France. Dr. Campbell focused on two case studies—that of Poligny and Amiens—to examine cases in which Colette’s desire for absolute poverty caused social and economic conflict. I found this such a strong, succinct reminder of the fact that the foundation of a monastic community could have profound consequences for the wider secular community—a mendicant may decide to give up all their property, but that doesn’t make the need for basic necessities go away.

Kimm Curran (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) presented a typology of the material culture and remains of Scotland’s female monasteries. She divided them into those for which no physical evidence remains; those which have been excavated to show some ground plans and items of interest; those which have some extant remains; and the lone surviving extant structure, that of Iona Priory.

Tracy Collins (University College Cork) was not present, having recently given birth, but her paper was read by Judith Frost. Her paper presented an “engendered archaeological approach” to the female monastic orders of later medieval Ireland, arguing that nunneries were not deviant to the male approach to monasticism, but simply different. I found the analysis of monastic layout here particularly interesting—the three remaining cloister-planned Irish nunneries are very distinct from the “ideal monastery”, and there is no indication of substantial precinct walls.

Linsey Hunter (University of St Andrews) presented the conference’s last paper. She undertook a diplomatic analyis of the acta of female Cistercian houses in Scotland, with a particular focus on the monastery at Coldstream. Dr. Hunter compared the language used in warranty clauses before and after the introduction of the Common Law in about 1250, and argued that Cistercian nuns were at the forefront of legal innovation at that period.