It’s been something of an Anglo-Saxon long weekend here at the University of Iowa! On Friday, of course, we had Hilary Fox’s lecture on mental illness in Old English literature; yesterday, it was the turn of Stacy Klein (Rutgers), who gave a talk entitled “The Militancy of Gender and the Making of Sexual Difference in Anglo-Saxon Literature.”

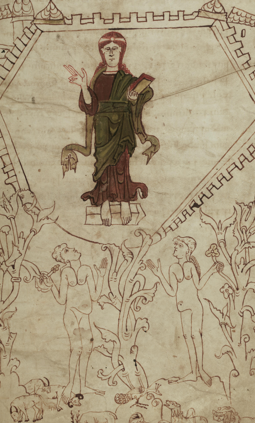

Professor Klein’s talk looked at how the Anglo-Saxons understood sexual difference—what it was that they believed made a man masculine or a woman feminine. She argued that while discussions of this topic have been hard for scholars to find in Old English literature, this is not because Anglo-Saxon writers failed to address issues of eroticism, romance or gender, but because modern people have failed to adequately understand their conceptual categories. To be male or female in Anglo-Saxon England depended not so much on sexuality or the body (indeed, bodily difference was considered to be a result of the Fall—see the image of a prelapsarian Adam and Eve above, Bodleian MS Junius 11) as it did on a particular relationship with militancy—the focus on warfare exhibited in the sources is not a barrier to our understanding of Anglo-Saxon gender, but rather one of the primary conceptual categories through which they expressed an understanding of sexual difference.

Some of the concepts with which Klein was engaging will be familiar to those who study medieval gender—the concept of the woman transcending her gender as one of the milites Christi is a common motif in Old English hagiography, and much has been written about transvestite saints and how gender might be normative but not entirely binding. Yet at least as someone who knows nothing about Old English, there was much here that was new to me. I found Klein’s discussion of the etymologies and variable meanings of OE words like wíf and mann to be fascinating, particularly in terms of their fluidity and their connotations of cloaking or covering. Sexual difference for the Anglo-Saxons was a spectrum across which women, at least, could move. Likewise the riddles which she discussed, one of the places in Old English literature in which we can see the discussion of gender which might be missing elsewhere—here we see sexual difference and sexuality being projected onto inanimate objects, sexual difference being largely depicted in the non-human world, which if I understood Klein correctly is not something which Anglo-Saxonists have investigated much before.

The big point of hesitancy in all of this was one which Klein herself raised: how do these literary gender paradigms relate to actual cultural practise? Did they open up new possibilities for women, did they reify maleness and devalue femininity, or were they serve more to create new gender roles for men? Here I think we end up back at that key point from Hilary Fox’s lecture on Friday—that people are capable of holding many contradictory ideas and values at once, and that there may not have been one single way in which these more abstract ideas about gender informed material actions. It’s a question which Professor Klein will no doubt explore in her forthcoming book, which is one I will definitely have to remember to seek out in the library.