I was one of the thousands of people who gathered in Seneca Falls this past Saturday to participate in the Women’s March. This was just one of a whole series of popular protests which took place across the United States, but the gathering at Seneca Falls had a particular poignancy—because in this small, western New York town in 1848, the first convention aiming “to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman” was held.

Almost 15,000 people gathered around the site of that first meeting before the march got underway, listening to an inspirational roll call of famous feminist activists—first wavers like Sojourner Truth and Lucretia Mott, second wavers like Gloria Steinem, and on. As a medievalist, this got me thinking about other times, other places. How far back could that roll call of women stretch?

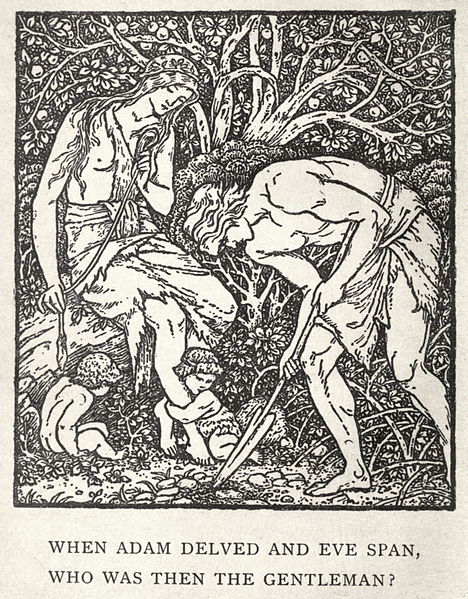

The answer is pretty far, but pretty tenuously. What sources we have for popular protest in the European Middle Ages are sparse. We know that people went on strike as far back as the thirteenth century. For example, crop failure and warfare pushed many Irish peasants to the brink of starvation in the 1290s, and the noblemen who made up the Irish parliament heard that “servants, ploughmen, carters, threshers, and [others] refuse to serve about the services for which they were accustomed to serve, on account of the fertility of the present year.”

Yet spontaneous popular protest was much less common in the medieval period than it is now, and the actions of these nameless people are known to us only through the records left behind by the rich and powerful, who cared about the desperation of peasants mostly inasmuch as it affected them, and who paid even less attention to the worries and concerns of women. Protesting women as distinct figures are a minority in the pre-Industrial West, and a rarity in the medieval world—after all, well-behaved women weren’t supposed to make their voices heard in public. There are few figures in the Middle Ages like the crowds of women who marched on Versailles in the early days of the French Revolution.

This, of course, doesn’t mean that medieval European women weren’t involved in protests. Many of them might be hidden in the crowd, so to speak: one of the many nameless gens, populares, communeté who are referenced in narrative accounts. Sometimes the sources provide glimpses of groups of women working together to combat unfair conditions. For instance, the people of the important trading city of Bruges revolted against an unpopular occupying French garrison in 1302, an event that’s become known as the Matins of Bruges. Eyewitnesses wrote that the city’s women fought ferociously against the French, “slicing [them] to pieces like little tunny fish (tuna)” and climbing up onto the rooftops in order to hurl the stinking contents of their chamber pots onto the soldiers below. Women marched with men and children during the peace movement of Parma in 1331 as they called for the overthrow of a despised ruler, chanting “Peace, peace” and “Down with the taxes and gabelles (salt taxes)!”

Most of the better documented cases of protesting women, though, come from late medieval Britain. Thirty women’s names appear on the pardon rolls for those involved in the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381. In 1427, a woman from the Stokkes—the market in London where meat and fish were sold—led an all-women’s march on Parliament to deliver a petition to its members, rebuking Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, for his ill-treatment of his wife and his open adultery. He was, they claimed, bringing the whole country into disrepute. In the English towns of Norwich and Yarmouth, women led riots in 1528 and 1532 over the high price of food; their leaders were publicly whipped in the marketplace.

Yet one of the key ways that women could have political influence during the medieval period wasn’t to form a group: it was to act individually, to intercede with the powerful on behalf of others in need. This form of action was mostly open to women of high social rank, particularly queens. They drew heavily on biblical imagery to frame their intercessory actions, wanting to be seen as a new Esther, pleading with her husband, the Persian king Ahasuerus, to spare the Jewish people, or as echoing the Virgin Mary, who as a heavenly queen was believed to persuade God to help the faithful on Earth.

An awareness of these tropes was why in 1275, a group of the townspeople of St Albans would approach the coach of Eleanor of Castile, consort of Edward I of England, pleading for her help in resolving their dispute over tithe obligations to the abbot of the local monastery. They sent a delegation (headed, interestingly enough, by a spokeswoman) and presented Eleanor with a letter stating that “all [their] hope” remained in her as it did in “that Lady (Mary) who is full of mercy and pity.” (en ky tote nostre esperaunce remeynt a touz iours cum a cele dame ky pleyne est de misericorde e de pite.) Marian imagery was clearly to the fore here. To this example of queenly action can be added many others. In 1264, for example, Violante of Aragon, wife of Alfonso X of Castile, pleaded for tax concessions to be granted to towns in the Extremadura region while she was attending the Cortes (main legislative assembly). The pregnant Philippa of Hainaut, in a very famous case, successfully persuaded her husband Edward III of England to spare the lives of the Burghers of Calais in 1347; she claimed that executing the men would harm her unborn child. (Sadly, her son would die while still an infant).

Some queens even understood the power of street protest. Isabelle of Hainaut, queen of France, may have died shortly before her twentieth birthday, but she had already learned how to be a canny political operator. Married to Philippe II of France when still a child, she became aware that he was trying to repudiate her, something which would seriously damage both her reputation and the political standing of her family. So in 1184, at just fourteen years of age, Isabelle appeared in public dressed as a penitent with her hair loose and uncovered, and walked barefoot from church to church in prayer while dispensing alms to the poor—a PR master stroke which won popular opinion over to her side and sent crowds to chant outside the royal residence in support of her. Philippe was shamed into treating his young queen better.

All of these royal women—Eleanor, Violante, Philippa, Isabelle, and many more—would have been very sensitive to sentiments like those expressed by the thirteenth-century English theologian, Thomas of Chobham. In a penitential text, Thomas wrote that “no priest is able to soften the heart of a man the way his wife can […] and if he is hard and unmerciful, and an oppressor of the poor, she should invite him to be merciful.” Women, in other words, were believed to have particular powers of moral persuasion in the Middle Ages. When they could act—in public, in person—they could get results.

There’s no singular inspirational lesson to be learned from this look at women and protest in medieval Europe—no clear tradition to be imitated, and some actions to be actively avoided. (I’d far rather make a placard or some phone calls than slice my opponents “to pieces like little tunny fish”!) Few women have the social status and authority of a queen, and even a queen-consort’s power was hampered to a certain extent by how much she could persuade men to agree with her. Unlike Thomas of Chobham, I don’t even believe that women are better suited than men at encouraging moral uplift in others—except perhaps inasmuch as experiencing oppression can make some women more aware of how societal forces affect them and others.

No singular lesson to be learned, except perhaps this: that when women organise, and agitate, and raise their voices, then as now, they can get things done.