I think we need to coin a term for the specific kind of exhaustion that hits the day after the IMC.

Session 8: Transforming Women: Gender and the Creation of the Early Franciscan Tradition

“Lady Jacopa and Franciscan Mysticism: Completing the Image of Francis as an Alter Christus”

Darleen Pryds, Franciscan School of Theology (Paper read in absentia)

This paper explored the contested ways in which Jacopa de Settesoli, a follow of Francis of Assisi, was represented in Franciscan historiography and hagiography. Darleen Pryds argued that some Franciscan administrators tried to excise Jacopa’s presence at Francis’ deathbed for reasons of propriety—the official life of Francis, written in 1260, omitted her for instance. However, other accounts did include her, representing her as the Mary Magdalene or the Magi to Francis’ Christ. This, Pryds claimed, allowed for the construction of a more theologically satisfying narrative which paralleled biblical texts more closely, as well as allowing for more pathos and drama.

[Image right: Jacopa de Settesoli, fresco in basilica of St Francis, Assisi. Credit]

“The Identities of Margherita Colonna in Medieval Rome”

Lezlie Knox, Marquette University

Margherita Colonna is a rather obscure figure in Franciscan history. However, Lezlie Knox, drawing on her work on two vitae of Margherita’s that are preserved in draft form in a fourteenth century manuscript (Bibl. Casanatense MS 104)—a study which she’s carrying out in conjunction with Sean Field—argues that Margherita’s relative obscurity is due more to the fact that her religious identity defies easy categorisation according to modern scholarly interests, and because of medieval tensions that worked against her canonisation, than because she’s unimportant. Margherita seems to have identified more with Francis than with Claire of Assisi, as we might expect if affinity follows gender. In addition, Margherita was a member of the powerful Roman Colonna family, which disagreed internally as to whether she should be allowed to follow a religious vocation—and, it seems, as to whether canonisation should be sought for her. The Colonna were also at odds with the papacy, and so it’s no surprise to find that Margherita fades from Franciscan collective memory after her death.

“Transforming Clare’s Rule: The Evolution of Colette of Corbie’s Constitutions”

“Transforming Clare’s Rule: The Evolution of Colette of Corbie’s Constitutions”

Anna Campbell, Graduate Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Reading

Anna Campbell contrasted the text of Colette of Corbie’s Constitutions—the “official” face of the Colettine reforms—with an earlier text, the Sentiments, drawn up in 1430. Here, Colette’s thoughts on reform are expressed in the vernacular and in a less legal manner. Campbell argues that by comparing the Sentiments, the Constitutions, and Clare of Assisi’s form of life in terms of structure and content, we can more explicitly see how Colette drew on Clare’s ideas during the process of reform.

[Image left: Colette and the pope. From vita of Colette of Corbie. Ghent, Bethlehem Convent of the Poor Clares, MS 8]

Session 93: Moving More Online: Strategies and Challenges for Using Technology in the “Classroom” (A Roundtable)

A roundtable discussion with Kate McGrath (Central Connecticut State University); Thomas R. Leek, University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point; Máire Johnson, Elizabethtown College; Andrew Reeves, Middle Georgia State College; Valerie Dawn Hampton, Western Michigan University/University of Florida; and April Harper, SUNY–Oneonta.

I live-tweeted this roundtable, and you can find those tweets aggregated here in this Storify.

Session 99: Women and Power to 1100 (A Roundtable)

A roundtable discussion with Julie A. Hofmann, Shenandoah University; Jonathan Jarrett, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham; Phyllis G. Jestice, College of Charleston; and Martha Rampton, Pacific University

Hofmann: Opens by asking if we need to rethink what we think power is before we look at women and power. #s99 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 14, 2015

Hofmann: Still grappling with legacy of 19th c. shaping what we think about gender, ethnicity; memetic misinformation #s99 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 14, 2015

Hofmann: A manifesto—can we dump current discourse? Even feminist discourse needs rethink in light of intersectionality #s99 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 14, 2015

Rampton: Works on magic, which is also a tricky term to define. Consensus that early medieval women had affinity with magic #s99 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 14, 2015

Rampton: Decline in perception of women's magic as potent doesn't improve women's standing but result of sidelining women #s99 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 14, 2015

Rampton: Need to talk more about deviance as a source of power #s99 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 14, 2015

Jarrett: We've been surprised by medieval women having power on a regular basis since 1908 #s99 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 14, 2015

Jarrett: Trend towards looking at women's lives as lived—with exception of v. few, that means in interaction with others #s99 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 14, 2015

Jarrett: Often struggle with problem that case studies aren't representative—problem with individuality. How to proceed? #s99 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 14, 2015

Jestice: We have lots of v. fine microstudies & v. large macro but little inbetween. We tend to overgeneralise #s99 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 14, 2015

Jestice: What is proper unit to study? How synthetic should a synthesis be—this panel *only* covers 500 yrs #s99 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 14, 2015

#Kzoo2015 #s99 Women's power as needing redefinition. Very interesting idea, must research/think on it

— Christina De Clerck-Szilagyi (@I_Historian) May 14, 2015

#Kzoo2015. #s99 Amount/type of sources shape the argument. I would add not just for the Middle Ages, but for everything

— Christina De Clerck-Szilagyi (@I_Historian) May 14, 2015

Very important point. RT @yvonneseale Rampton: Middle Ages not one big happy unit—specificity important #s99 #Kzoo2015

— Christina De Clerck-Szilagyi (@I_Historian) May 14, 2015

Session 153: Medieval Data: Prospects and Practices

“Workflows for Medievalists with Open Data Ideals and Closed-Source Texts”

Kalani Craig, Indiana University–Bloomington

Looking for patterns in text of Sulpicius Severus’ Life of St Martin with @kalanicraig in #s153 #Kzoo2015 pic.twitter.com/KuSbRC61Lk

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 14, 2015

Kalani Craig kicked off this session with a talk that was part an overview of the processes by which medievalists can engage in large scale analysis of texts, part passionate manifesto for the importance of open source ideals. Craig discussed the ways in which walling off digitised texts makes it more difficult for scholars at non-elite universities to carry out research, not to mention slows down their work. She then went on to discuss how to use natural language processors (which are often designed around the syntax of English) with an inflected language like Latin, and showed the network (seen above) created by her database about the appearance of the word ecclesia in a given corpus of texts. “‘I sign therefore I am’: Documenting Early Medieval Medici in Italian Charters, A.D. 800–1100″ Luca Larpi, University of Manchester

Luca Larpi speaks on databasing charters mentioning doctors in Italy 800-1100: http://t.co/4rrXv2vZ1p #s153 #Kzoo2015 pic.twitter.com/4IGNTFje35 — Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Luca Larpi presented the findings of his research—trawling through an amazing 17,000 charters from early medieval Italy in order to find the 178 which contain references to doctors. Larpi used these charters to create a database. While small, Larpi argued that the database gained in utility when used in conjunction with bigger databases such as ALIM. He also grappled with some of the issues of making databases out of fuzzy data, or out of conclusions which arose from judgement calls made as historians. In monographs, historians can provide a critical apparatus which calls the reader’s attention to the historical process—could an equivalent feature be provided in a database?

“The Archaeology of Anglo-Norman Rural Settlement in Co. Wexford, Ireland, ca. 1169–1400”

Brittany Rancour, University of Missouri–Columbia

Brittany Rancour discussed the process of GIS analysis which she used to explore the preferences of Anglo-Norman settlers in Wexford. She used or created hydrology maps and maps of soil type, among others, to show a clear association of moated sites with nucleated settlements. The Anglo-Norman settlers also seem to have sought out soils which were rarer but were better suited for the kinds of agriculture which they practiced.

“Pointless Maps: Spatial Analysis with Fuzzy Data”

Amanda Morton, George Mason University

Amanda Morton talks about making fuzzy data of messy data—dealing with uncertainty #s153 #Kzoo2015 pic.twitter.com/oMOGBTz7yA

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Amanda Morton’s project involves mapping the Justinianic plague in the Byzantine world—which is no easy task. Much of her mapping work involves uncertainty or supposition, while also accounting for the biases of the ancient authors on whom she draws, and so Morton explored ways in which to represent fuzzy data on a map. Morton is drawing inspiration from modern epidemiologists’ maps of the ways in which ebola spreads, and from projects like the Literary Atlas of Europe which attempts to map fictionalised versions of real landscapes.

Friday

Session 226: The Nature of the Middle Ages: A Problem for Historians? (A Roundtable)

“The Material Turn”—Robin Fleming, Boston College

“The Study of the Middle Ages and the Dread Word Relevance”—Marcus Bull, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill

“Not Quite Fifty Years of Women’s History at Kalamazoo”—Ruth Mazo Karras, University of Minnesota–Twin Cities

“Changing Subjects in Medieval History”—Paul Freedman, Yale University

“‘Medieval’ People: Psyche?/Self?/Emotions?”—Nancy Partner, McGill University.

https://twitter.com/Lollardfish/status/599213970424213505

Robert Berkhofer introduces #s226—explains panel takes title from one held at very first Congress #Kzoo2015 pic.twitter.com/87kmMeOkAH

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

#Kzoo2015 #s226 starts with Robin Fleming urging material studies to become MATERIAL!

— Material Collective (@materialcoll) May 15, 2015

Fleming: Historians & material culture at #Kzoo2015 found in food & textile panels; but other historians not so good at using objects #s226

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Fleming: Urges more consideration of material culture—three steps. Step 1: People make things but things make people #s226 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Fleming: Step 2: read some theory on material culture, but back way into field by starting with beginnings in the 70s #s226 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Fleming: Step 3: Make new friends—avoid being lone wolf historian. Collab with people in "thing-oriented" disciplines #s226 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

#kzoo15 #s226 Marcus Bull (Thinking Medieval) on relevance #metakzoo

— Material Collective (@materialcoll) May 15, 2015

Bull: Attending #Kzoo2015 like attending General Chapter of order at period historians thought was decline but now reassess #s226

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Bull: Medievalists as the interdisciplinary hipsters (we were interdisciplinary before modernists ever heard of it) #s226 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

#Kzoo2015 #s226 m bull: relevance feeds off folk-psychological instinct for causality. #metakzoo

— Material Collective (@materialcoll) May 15, 2015

Bull is clearly not a fan of Guldi & Armitage's "History Manifesto" (http://t.co/nVRR0awez5) #s226 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

https://twitter.com/Lollardfish/status/599218721714999298

Bull: Medieval period worth studying because it's interesting and it's difficult (Greeted with laughter & applause) #s226 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

#Kzoo2015 #s226 Ruth Karras: not quite 50 years of women's history at Kzoo

— Material Collective (@materialcoll) May 15, 2015

Karras: Looked for women's history in old K'zoo programs—'71 had paper on women's lib in medieval lit. 1st full session '72 #s226 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Karras: Many paper titles clearly the origin of later important works on women's history (e.g. McNamara, Schulenberg) #s226 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

RM Karras reviews the history of women's studies at kzoo, including a call for "ovular" rather than "seminal" texts. #Kzoo2015 #s226 #fbf

— Material Collective (@materialcoll) May 15, 2015

#Kzoo2015 #s226 Karras: tension between studies of lay and religious women, balance seems to be shifting towards spirituality

— Material Collective (@materialcoll) May 15, 2015

Karras: Sees signs of mainstreaming of women's history, with papers on women appearing in more diverse panels #s226 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

#Kzoo2015 #s226 Paul Freedman gives us an overview of early Kzoo congresses: about 100 people attended the first! (see the programs online!)

— Material Collective (@materialcoll) May 15, 2015

Freedman: 565 panels at #Kzoo2015; only 13 on social-historical topics, of which 7 organised/populated by European scholars; decline? #s226

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Freedman: But Kzoo never strongly oriented towards historical—in history panels always more mentalité than material #s226 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

#Kzoo2015 #s226 Nancy Partner: everything medieval is a problem, starting with its very definition

— Material Collective (@materialcoll) May 15, 2015

Partner: Good riddance to Burkhardt—but what has replaced his ideas about the Middle Ages? #s226 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

#Kzoo2015 #s226 the iceberg self, barely visible in the social. is that us? our medieval subjects?

— karen overbey (@keoverbey) May 15, 2015

Session 229: Debatable Queens: (Re)assessing Medieval Stateswomanship, Power, and Authority

“Melisende of Jerusalem: Daughter, Sister, Wife, Mother, Queen” Erin L. Jordan, Old Dominion University (Image right: Coronation of Melisende, BNF MS fr 779)

Erin Jordan kicked off this session with a reassessment of the career of Melisende of Jerusalem. The traditional historiography accuses Melisende of refusing to give up the regency and thus usurping the throne from her son, Baldwin. However, Jordan argues, it was Baldwin who defied his mother’s rights—given the political situation and inheritance practices in force at the time, Melisende should be understood as a co-ruler and not as a regent.

“Isabeau of Bavaria (1370–1435): Pawn or Player?”

Tracy Adams, University of Auckland

Tracy Adams reminded us of the importance of returning to the primary sources with the reassessment of another royal woman, this time Isabeau of Bavaria. Adams finds no trace in the primary sources of the frivolous and greedy reputation which Isabeau holds amongst Anglophone scholars, and argues that this reputation comes from an overreliance on the conclusions of nineteenth-century French historians of republican sympathies who saw in the Germanic Isabeau a proto-Marie Antoinette. Adams argues that Isabeau should be reassessed as central part of the familial nature of royal power in this period, someone who was a player during her lifetime and who only became a pawn after her death.

“She Who Must be Obeyed: (Re)assessing the Statecraft, Power, and Authority of Yolande of Aragon (1381–1442)”

Zita Eva Rohr, University of Sydney

Zita Rohr’s paper spoke very much to the preceding one, as she discussed Yolande of Aragon—not only was Yolande a contemporary of Isabeau, but Yolande’s daughter, Marie of Anjou, married Isabeau’s son, Charles VII of France. Rohr looked at how royal women self-fashioned their reputations in order to succeed at their roles, and argued that Yolande projected herself against Isabeau in a very self-conscious way. Yolande was never a queen, but she became known Charles VII’s beau mère, which demonstrates a very pragmatic model of self-fashioning and statecraft.

Session 291: Debatable Rule:(Re)assessing Medieval Statecraft, Power, Authority, and Gender (A Roundtable)

A roundtable discussion with Theresa Earenfight, Seattle University; Kimberly Klimek, Metropolitan State University of Denver; Núria Silleras-Fernández, University of Colorado–Boulder; and Elena Woodacre, University of Winchester.

Zita Rohr introduces panel on medieval statecraft & gender #s291 #Kzoo2015 pic.twitter.com/3hIpdJMc47

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Earenfight: Even as feminists, we've tended to focus on Great Women, Great Deeds; but more nuanced arguments emerge #s291 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Earenfight: We qualify women's power as female, but not men's power as male—but this is unnuanced view of kingship #s291 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Earenfight: Power is agency with implications; but vocab is tricky as we saw yesterday in #s99—use so many diff words #s291 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Earenfight: Need to think of men as actors with same degree of subtlety as we think of women's authority, agency, power #s291 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Debatable rule r'table: Earenfight childlessness not necessarily a break on queen or ruler's power #RoyalStudies #Kzoo2015

— Dr Elena 'Ellie' Woodacre (@monarchyconf) May 15, 2015

Klimek: Looking at letters of women to/from Anselm of Canterbury—v familial & personal; argues this has political importance #s291 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Common denominator to medieval power seems to be relationship/network. Just like twitter. #Kzoo2015 #s291

— Dr. Lucy K. Pick (@lucykpick) May 15, 2015

More r'table: Klimek familial nature of power, communitas and familias instead of autonomy #RoyalStudies #Kzoo2015

— Dr Elena 'Ellie' Woodacre (@monarchyconf) May 15, 2015

Silleras-Fernández argues we should look at queenships from many perspectives, not be limited by labels #s291 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Silleras-Fernández: focus on two Mirrors written for Isabel I of Castile #s291 #Kzoo2015 pic.twitter.com/oA6E8y0gG9

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

More r'table: Sillaras-Fernandez 'mirrors' for Isabel of Castile, more virtuous when imitating male attributes #RoyalStudies #Kzoo2015

— Dr Elena 'Ellie' Woodacre (@monarchyconf) May 15, 2015

Woodacre asks what makes ruler debatable? Sees link between debatable rulers & succession mechanisms #s291 #Kzoo2015

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 15, 2015

Last r'table: me debatable rulers when succession order/rules contravened, debatable rulers undermine stability of the realm #RoyalStudies

— Dr Elena 'Ellie' Woodacre (@monarchyconf) May 15, 2015

Saturday

Session 360: Art and Technology in the Cloister and Castle I

“Castles, Cloisters, and Churches: Examining the Larger Context of Medieval Architecture”

William W. Clark, Queens College and Graduate Center, CUNY

Clark shows imaginary arch. created by excl. Hotel Dieu & other attached structures of Laon cathedral #s360 #Kzoo2015 pic.twitter.com/AYyPV1vUb5 — Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 16, 2015

William Clark’s talk explored a variety of different buildings, but mostly those which formed part of the complex of buildings around the cathedral of Laon. He argued that too often, architectural historians have tended to reconstruct churches and cathedrals which are imaginary in their isolation, stripped of their structural dependencies. Clark traced this tendency back to the lithographs produced by nineteenth-century scholars such as Alexandre Du Sommerard, and argued that scholars needed to move away from this mode of depiction.

“Activating Architecture: New Perspectives on Medieval Walls”

Maile S. Hutterer, University of Oregon

Ribbed vaults and pointed arches were frequently used in both secular and religious architecture in the Middle Ages, but flying buttresses were rarely used except on churches and cathedrals. Maile Hutterer investigated possible ways in which flying buttresses fit into the system of medieval building vocabulary beyond that of the ecclesiastical. Hutterer argued for a greater exchange between ecclesiastical and military architecture during the period 1160/80-1220 than has previously been recognised, with crenellations and fortifications echoing one another in both contexts.

“A Stone’s Throw: Durham’s Late Eleventh-Century Building Projects”

“A Stone’s Throw: Durham’s Late Eleventh-Century Building Projects”

Meg Bernstein, University of California–Los Angeles

Meg Bernstein discussed the symbiotic nature of the cathedral and castle at Durham, both constructed during the last decades of the eleventh century. She argued that the structures exist in a kind of “national tension” that was deliberately constructed—the cathedral’s architecture reflects Anglo-Saxon influences due to its links to St Cuthbert, while the castle is more purely Norman in its style. In places where interaction with the local population was necessary, it was pragmatic to give a nod to the local architectural traditions; but in his own private residence, the Norman bishop was better able to indulge his own preferences.

(Image right: Durham Cathedral and Castle as seen from the banks of the river. Credit.)

Sessions 404 & 463: Nunneries in Medieval Europe: New Historiographical and Methodological Approaches I & II

“Debating Reform in Tenth- and Early Eleventh-Century Female Monasticism”

Steven Vanderputten, University of Gent

“Redefining Female Leadership and Patronage in the Iberian Monasteries of the Order of Fontevraud: Tradition and Renewal”

Laura Cayrol Bernardo, EHESS

“Dominican Nuns’ Agency in the Definition of Art, Architecture, and Liturgical Performance in Castile”

Mercedes Pérez Vidal, Univ. Nacional Autónoma de México

Since these back-to-back sessions were two parts of a whole, I live-tweeted them as such; you can find them aggregated in this Storify.

Sunday

Session 535: Locating the Early Irish Monks and Saints

Session 535: Locating the Early Irish Monks and Saints

“The Transmission and Uses of the Amalarian Liber officialis and the Collectio canonum hibernensis in the Monastic Environs of Brittany, Sankt Gall, and Reichenau”

Shannon O. Ambrose, St. Xavier University

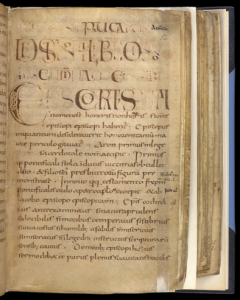

Shannon Ambrose assessed some of the early medieval manuscripts of the Liber officialis and the Collectio hibernensis—six of the former and nine of the latter—in relationship to one another. Ambrose read them in light of Carolingian attempts to displace older Celtic traditions. These manuscripts should not simply be considered in isolation as part of the corpus of one individual monastic community, Ambrose argued, but more fruitfully as part of complex process of inter-regional incorporation and adaptation.

[Image left: BL Royal 5 E XIII, f.52. Collectio hibernensis excerpt. Source]

“Coptic Peregrinations Revisited: Locating Egypt in the Early Irish Monk”

Westley Follett, University of Southern Mississippi

Follett spoke in reaction to previous scholarly speculation, by people such as Robert K. Ritner, as to whether Egyptian monastics has directly influenced their counterparts in early medieval Ireland. Follett is an avowed sceptic. While there may have been indirect intellectual influence through the writings of John Cassian, and a general admiration of the desert fathers, Follett found no sign of the direct influence posited by earlier historians. Follett argued for a reassessment of the kinds of evidence that have been marshalled in favour of the arrival of Egyptian monks in Ireland—such as the Ogham stone in Cork which was erroneously believed to contain an inscription asking for prayers for ‘Olan the Egyptian’—as nothing more than a wistful longing for the exotic.

“Mapping the Desert: Using the Toponymy of Díseart and Cill to Map the Early Medieval Irish Monasteries”

Brian Ó Broin, William Paterson University

Brian Ó Broin set out to map the terms díseart and cill in Irish placenames, to see if he could prove once and for all the long-held idea that the former term is associated with the east coast and the latter with the west. However, Ó Broin soon found that this methodology was problematic, and the word díseart even more so. It’s traditionally translated as a ‘desert’ or wilderness area to indicate inhabited by an early medieval hermit, but this sense doesn’t fit with how the word is used in some texts (how can a díseart then have a door, for instance?). Ó Broin argued that the term as used in place names is actually a late medieval one, used to indicate a (perceived) association of a small abandoned—deserted!—monastic site with the memory of a particular person. With few exceptions, díseart appears in medieval Irish texts as a place identifier in the form of Díseart X, where X is a person’s name.

.@brianeanna shows distribution map of díseart placename, then says illusory—term’s actually late. #s535 #Kzoo2015 pic.twitter.com/vQWbIqyhFm

— Yvonne Seale (@yvonneseale) May 17, 2015

Session 558: Moving Women, Moving Objects II

“Networks of Gold and Silver: The Collecting of Isabella of France”

Anne Rudloff Stanton, University of Missouri–Columbia

“Women Collectors and Patrons: Toward a Cartography of Exchange in the Late Middle Ages”

Diane Antille, Université de Neuchâtel

“Empress Matilda and the Valasse Reliquary Cross: From the Holy Roman Empire to the Plantagenet Realm”

Nicolas Hatot, Musée des Antiquités, Rouen

I live-tweeted this session, and you can find those tweets aggregated in this Storify.