Dorothy Dunnett’s Lymond Chronicles may be one of the most influential series of novels that most people have never heard of. The books follow nobleman Francis Crawford of Lymond on his high-stakes adventures across mid-sixteenth century Europe from his native Scotland to Russia, from France to Malta to Turkey. Although many later writers, working in many different genres, have acknowledged a sincere debt to Dunnett’s novels, they’re very much a cult favourite. (When I first devoured them, back in my undergrad days, I had to track down each volume in various secondhand bookshops across Dublin. Thankfully they’ve just been reissued by Vintage in paperback, reset with nice crisp type no less.)

Reviewers did notice the books when they first appeared—in six volumes between between 1961 and 1975—though in ways which gave short shrift to some of Dorothy Dunnett’s most memorable characters. In 1964, a New York Times reviewer recommended Queen’s Play as a “first-rate historical”, and described Lymond as a cross between Golden Age detective Lord Peter Wimsey and action star James Bond. The reviewer mentions the book’s female characters only as motivations or obstacles for Lymond: the redoubtable Mary of Guise, Dowager Queen of Scotland, is described as someone who “offer[s] nothing, but expect[s] the impossible.” The Boston Globe’s reviewer described Pawn in Frankincense (1969) as possessing “a full complement of beautiful women, brave men, villains, traitors, sadists and one marvelously drawn plain-Jane English girl of 15.”

No one who’s read the series can deny that Lymond—in all his melodramatic, polymath, tortured glory—leaps off the page of these books. But by focusing so tightly on him, those reviews implicitly dismiss some of the most compelling women characters you’re likely to find in print.

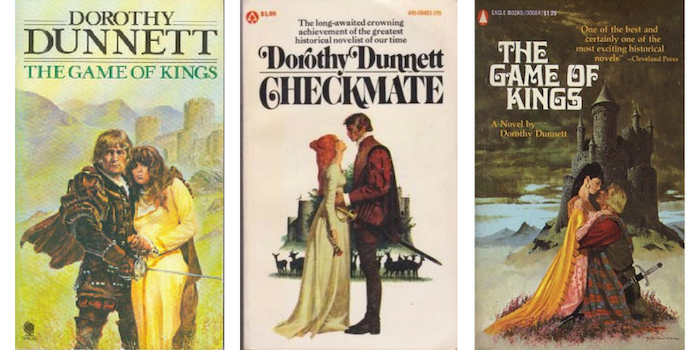

Though the covers of the early editions of the books make them look like trashy bodice rippers populated by people with some truly terrible hairstyles, the Lymond Chronicles are anything but. They’re densely plotted, allusive political novels—full of derring-do and desperate chases across French rooftops, yes, but Dunnett is always aware of the complexities of the world in which they take place.

These are not sentimental books.

When I first read the series, I was enthralled by the women of the Lymond Chronicles because of how much they got to do. Yet to be honest, my younger self probably thought that Dunnett had taken some historical liberties in giving them so much to do, and perceived them as women “ahead of their time.” It’s only now, after several years spent studying the history of women in pre-modern Europe, that I better understand just how much Dunnett’s female characters have both feet firmly planted in a sixteenth-century world.

Most of these women are members of the elite—from the gentry, nobility, or royalty—accustomed to wielding the power their social status and wealth affords them. A lot of historical literature gives us “strong female characters” to identify and empathise with, women who are achingly aware of the patriarchal oppression they face and are overtly struggling against it. Yet much more plausible to me—and uncomfortable, and interesting—is reading about how a woman wields power within both the gendered limitations of her society and of her own beliefs about what she can and should do.

Pivotal characters like Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox (based on a historical figure) and Oonagh O’Dwyer (entirely fictional) aren’t what you could call “feminist”, either in their personal beliefs or in their respective narrative arcs. However, they are both in the possession of firm political convictions, whether those are in the service of themselves (as with the femme fatale-esque Countess of Lennox) or in the service of nation (as with my countrywoman Oonagh). These are women who are entirely capable of thinking in subtle, tactical ways, and Dunnett explicitly presents them as such.

Nor are they isolated examples. Dunnett provides a marvellous description of the political nous of Mary of Guise, the Scottish Queen Dowager, writing that the “thick oils of statesmanship” ran in her veins, and that she “rarely handed through the door what she could throw in by the cat’s hole.”

Without giving too much away—because these are books you want to go into unspoiled—the choices these women make at the intersection between their particular circumstances and broader systemic patterns of power, between their strengths and others’ weaknesses, are thoroughly fascinating.

(Also sometimes thoroughly upsetting. Do not start reading the fourth book, Pawn in Frankincense, if you don’t have a quiet room to shriek in as you go. Maybe also a couch to lie on.)

This isn’t to say that either the characters or Dunnett’s framing of them is flawless. Lymond has a relationship with his mother, Sybilla, which could most charitably be described as “troubled.” As scholar Deirdre Serjeantson has pointed out, the readings which gave Lymond such a command of a wide swathe of literature also inculcated in him “an oppressive sense of what was required in respect of female virtue.” Although Lymond’s perspective on women’s sexuality (and indeed his own) shifts somewhat as the books progress, and as he comes to better understand Sybilla and her history, he’s not really what you could call the sixteenth-century version of “woke”.

Yet neither Lymond nor pretty much any other character in the Chronicles is taken aback at the idea of women being influential or involving themselves in politics—whether dynastic, domestic, or international. That was simply what elite women in early modern Europe did, as a lot of recent scholarship has shown.

In the sixth book, Checkmate, one of the main characters, Philippa Somerville, reflects that:

She had been led into behaving like a female. And she was being dismissed as a female. But she had charge of his good name, although he might not know it…

Here she’s responding directly to events happening around her, but Philippa’s observation also holds true more broadly. Women in medieval and early modern Europe could, and did, have charge of the “good name” of their husbands, families, dynasties, and nations—and in doing so they were very much “behaving like a female.” No wonder that in the same book, Sybilla scolds Lymond back to a sense of his responsibilities by asking him if he thought she’d brought “any child into the world to live for himself alone?”

Sybilla, Margaret, Philippa, Marie, Oonagh, Mariotta, Catherine, Marthe, and the many other women who fill the pages of the Lymond Chronicles may not have caught the attention of reviewers back in the 1960s. That’s not particularly surprising.

Neither is this: to pay close attention to what’s going on in a high-stakes, high-wire plot and to find women at the heart of it all.

Great blog, now do one for the House of Niccolo- Marian, katelina, Gelis, Primaflora, the Naxettes. Maybelie.