A wall cast a long shadow across the recent U.S. presidential election: the 1,954 mile-long wall which Donald Trump has promised will soon stretch the length of the U.S.-Mexico border. Whether a foundation will ever actually be dug for this wall, or what that wall should look like, are matters of hot debate right now. Archaeologists and historians have pointed out that there is little historical precedence for the efficacy of these kinds of border walls. Still, its proponents are adamant that a wall is necessary to preserve the integrity of the United States: that fearsome and alien things lurk just on the other side of the border, that a wall can be a firm dividing line between “us” and “them”.

This understanding of a wall—one built as much out of rhetoric and identity as it is out of bricks and mortar—has a long history. Medieval Europeans’ sense of themselves was defined in part by what they were not. They believed that they were normal, while the far reaches of Africa and Asia were inhabited by all sorts of weird and wonderful creatures barely recognisable as people. The blemmyes had no heads but rather faces that were embedded in their chest; the homodubii were a kind of centaur with the body of a donkey; the panotti had ears so large that they could wrap them around their bodies like blankets, protection against the cold of their homeland in the far north. The most ferocious of these quasi-humans were the peoples of Gog and Magog, cannibalistic invaders who were kept at bay only by the walls which had been built around them.

Gog and Magog loomed large in the medieval imagination. They appear in the Hebrew Bible (Yechezkel/Ezekiel 38-39), in the Christian New Testament (Revelation 20:7-8) and the Qur’an (Surah Al-Kahf, 83-101). While the exact details of who they were and what actions they were prophesied to carry out varied, all faith traditions agreed that the inhabitants of Gog and Magog were a wild and fearsome people who were held at bay for now, but who would one day help to bring about the end of the world. Though relatively obscure figures in religious scripture, they took on a life of their own in popular legends and stories, particularly in the series of interconnected and apocryphal tales known as the Alexander Romances.

According to many medieval tales—based in part on the stories of the first-century CE Jewish historian Josephus—Alexander the Great had come across wild and unclean peoples as he and his forces pushed eastwards across Asia. To keep these peoples from destroying humanity, Alexander drove them between two huge mountains, then prayed that God would push the mountains together and so imprison them. His wish was granted. This story was repeated and embellished on in later influential medieval texts, such as the seventh-century Syriac Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius and the Alexander Romance cycle, where the peoples imprisoned by Alexander became identified with Gog and Magog. In some of the stories, Alexander orders his army to build a set of gates across passes in the Caucasus mountains to keep back these apocalyptic forces. These gates—variously described as of iron or bronze—were coated with a fast-sticking kind of oil.

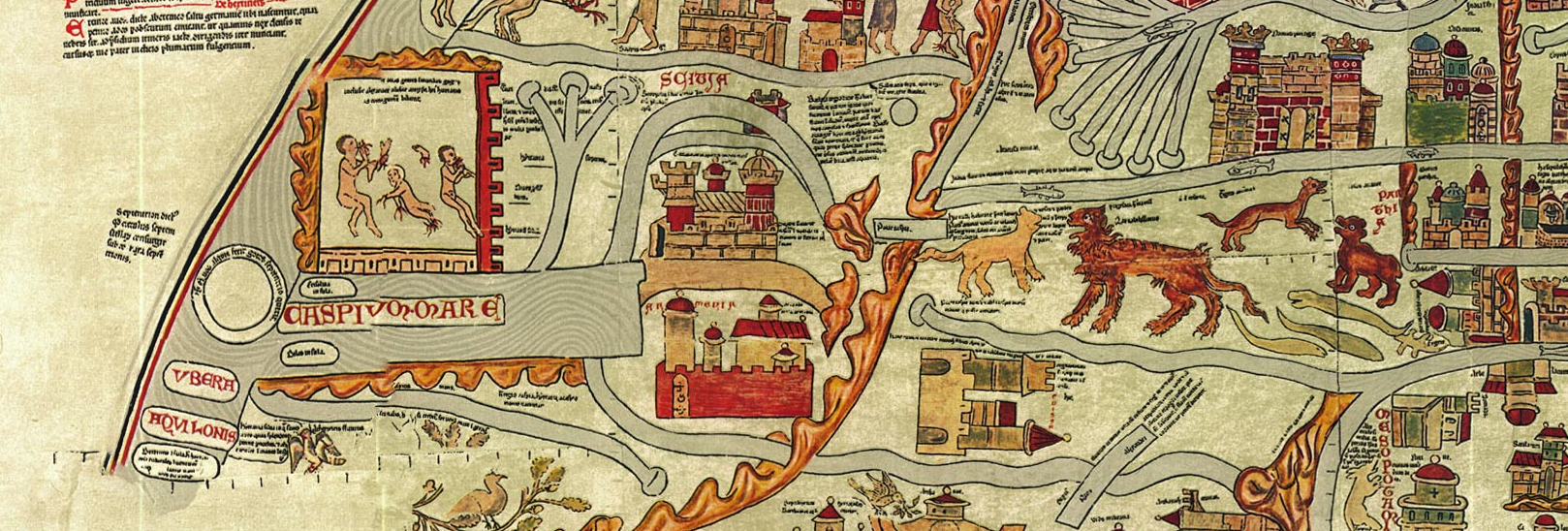

As the Middle Ages progressed, western Europeans began to look beyond their home regions, to become aware of the scale of the globe in a way they had not in generations. They produced mappa mundi, maps of the world, of increasing complexity and sophistication. Gog and Magog appeared on many of these maps, though the location of their homeland and their affiliation shifted according to contemporary concerns and fears.

The Ebstorf mappa mundi (a detail of which appears in the header image of this post), shows a walled-off area labelled Gog and Magog where the monstrous inhabitants are in the act of devouring a disfigured victim. On the border of the same map, closer to Europe, there is also text which describes the “city and island of Taraconta which is inhabited by Turks of the race of Gog and Magog, a barbarous and wild people who eat the flesh of young people and aborted foetuses.” Other maps identified Gog and Magog with the Lost Tribes of Israel, showing iudei inclusi (“enclosed Jews”) or “Red Jews” on maps of Asia and creating artwork depicting Gog and Magog that drew on overtly anti-Semitic imagery. Hostility towards Islam and Judaism clearly drove these identifications on the part of medieval Christians.

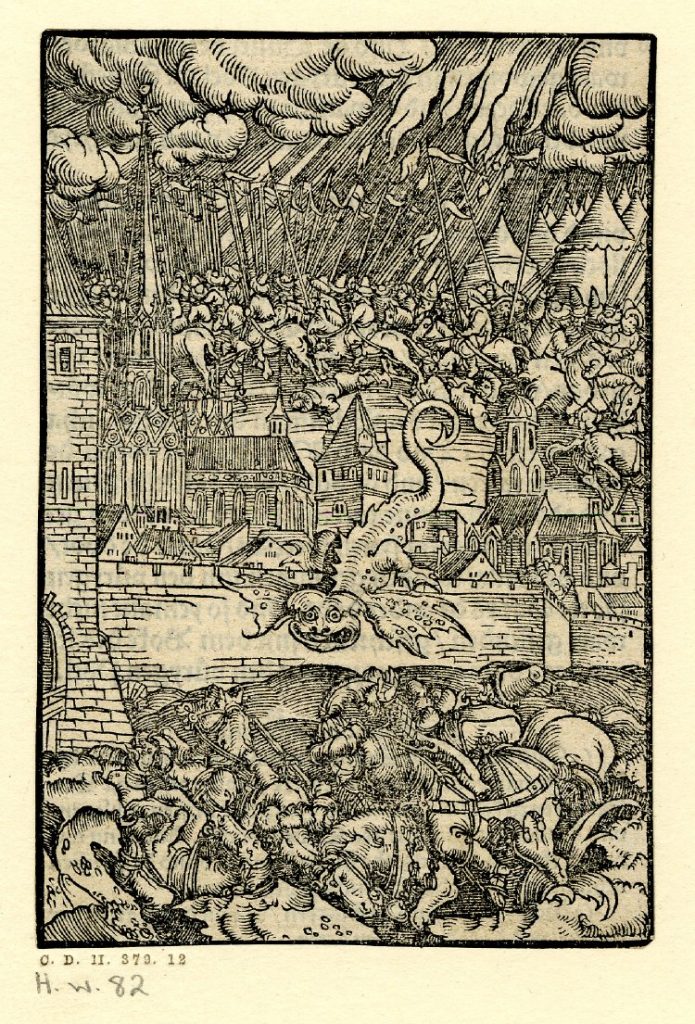

When the Mongol empire was at its height in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, many Europeans came to the conclusion that they—appearing suddenly out of the east and sweeping all before them in the creation of an empire of unprecedented size—were the peoples of Gog and Magog, or sometimes descendants of the Lost Tribes of Israel who had abandoned Judaism. What else could they be but harbingers of the apocalypse? Not only were they conquerors but their way of life was alien from that of the vast majority of Europeans.

In an age of Google Maps and accurate cartography, it’s tempting to consign the land of Gog and Magog to the past, as simply yet another funny and ignorant quirk of the medieval European worldview. Yet to do so is to ignore that even at the highest political levels, many nowadays still believe that was was written in the book of Ezekiel will literally come to pass, even if they don’t imagine a lost, walled-off city somewhere in Eurasia. For instance, in 1971, Ronald Reagan—then governor of California—explicitly stated that the “communistic and atheistic” USSR was the fulfilment of the prophecy in Ezekiel. It’s been claimed that in a 2003 phone call to Jacques Chirac, George W. Bush cited end-time prophecies about Gog and Magog in an (ultimately futile) attempt to persuade the French to participate in the invasion of Iraq.

It is also to overlook the ways in which modern people are still capable of making sharp divisions between “us” and “them” based on little if any evidence. Political rhetoric turns desperate refugees into an overwhelming horde; it conjures up a criminal threat poised just the other side of the border. Whether in medieval Europe or the modern West, people tend to define themselves by what they are not—but as was the case with Gog and Magog, these fears do not truly originate behind distant mountains in lands with unfamiliar names. Their origins lie far closer to home.