Much ink has been spilled on the marriage of Prince Harry of Wales and American actress Meghan Markle over the past few months, and a good gallon or three of that ink has been used to write about connections between the wedding and the Middle Ages: everything from the venue, the late medieval St George’s Chapel (“a place of prayer, pageantry and ritual since the 15th century“), to how fruit cake has been served at royal weddings for several centuries (“optimally suited to an era before refrigeration“), to Markle’s own distant royal ancestry (“American star can trace family connections to Edward III and Jane Seymour“), and the calligraphic instrument of consent issued by Queen Elizabeth permitting the union (“elaborately ornate, written on vellum“).

Ordinarily, I love a good newspaper piece about the connections between the Middle Ages and modern events, but I have to admit to more than a bit of fatigue about this royal wedding. As with the marriage of Prince William and Kate Middleton in 2011, this is an expensive, tax-payer-funded affair whose pageantry is used to help shore up popular support for a hierarchical, monarchical system. (In fact, as I write this post, I’m listening to a reporter on the BBC World Service asking a pro-republic Australian if he won’t reconsider his stance because “Isn’t this [the wedding] romance, isn’t this fun?”) Even Americans are throwing viewing parties, with one woman in Ohio justifying watching it while all dressed up with “Who doesn’t get excited about a little romance? And then all this special royalty stuff, it doesn’t happen every day. And I just think it’s kind of exciting.”

The implication is that a royal wedding, with all its medieval-lite trappings and street parties and fashion ogling, is a harmless bit of fantasy—a way that the public gets to share in a Disney-esque “happily ever after.” If you don’t agree, well, you’re a bit of a curmudgeon.

The thing is, of course, that we know that a royal wedding doesn’t automatically equate to a royal happily ever after. This was true for Harry’s own parents, and it was true for centuries before that. Marital discord and breakdown aren’t new phenomena, symptoms of a modern age. They happened in the Middle Ages, too, for royals and commoners alike. (Historians studying English court records have even identified an annual post-Christmas rush in annulment and separation cases dating back to at least the fourteenth century.)

For Christians living in western Europe during much of the Middle Ages, getting married was a relatively simple affair—a consenting exchange of vows between two people was all that was needed to legitimate a marriage in the eyes of the Church. Getting unhitched, however, was a much more complicated affair, since over time church teaching increasingly stressed the indissolubility of marriage. There was no Christian divorce as we understand it—no legal ending of a valid marriage—in the Middle Ages. However, in certain circumstances the Church could grant an annulment (divortium ad vinculo) in cases where a spouse was unable to consummate the marriage, where it was discovered that the spouses were too closely related to one another, or where one spouse had been unable or unwilling to consent to the marriage. Legal separation (divortium a mensa et thoro) could be granted on the grounds of adultery, heresy, or cruelty and allowed the couple to live apart, though neither could remarry during the other’s lifetime. Annulments and separations were rarely granted, though. The Church stood firmly by its interpretation of scripture: “Let not man therfore put a sunder, yt which God hath coupled together.”

There were, however, some notorious cases of marital difficulties among the royalty of medieval Europe. The tenth-century ruler Lothair II of Lotharingia tried to get rid of his childless wife Teutberga (d. 875) after two years of marriage in order to marry a mistress who had already borne children by him. He made lurid and it seems entirely false accusations about poor Teutberga, accusing her in church court of witchcraft and incest with her own brother in an attempt to secure an annulment. Even threatened with torture, Teutberga refused to admit to any of the charges. She withstood being scalded with boiling water, at which point the Church called an end to proceedings and ordered Lothair to take back his wife and acknowledge her as his legitimate queen. (Teutberga went on to survive him.)

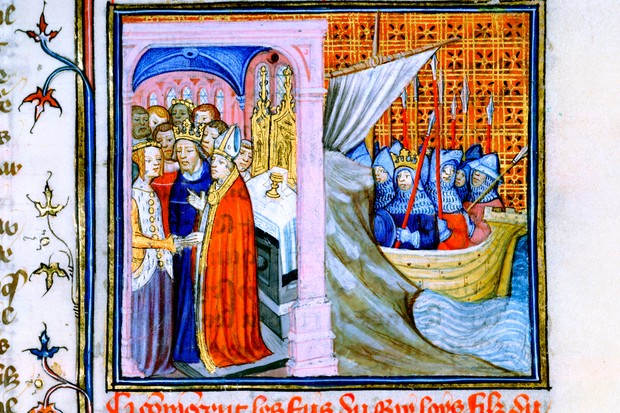

The honeymoon period for Ingeborg of Denmark (1174-1237), who arrived in France in 1193 to marry King Philip II, was even shorter. Philip was already a widower—his first wife, Isabelle of Hainaut, having died young in childbirth—and he wanted more children to secure the line of succession. Ingeborg and Philip’s wedding night must have been one of the worst in history, because the very next morning Philip tried to send his new bride back to Denmark. His actions have given rise to a lot of later speculation among historians: was Philip unable to perform sexually and so acting out of humiliation? Did Ingeborg have some hidden deformity he found repulsive? Was Ingeborg too feisty for him, or had Philip’s estimation of the political worth of the match changed abruptly? We don’t know. But we do know that Ingeborg refused to go without a fight, seeking refuge in a convent in Soissons and sending messengers to plead her case with the pope. Although the pope backed Ingeborg, Philip refused to change his mind and entered into a bigamous third marriage with the German princess Agnes of Merania. His disregard of papal authority, his very public harshness towards Ingeborg and his stubbornness in marrying Agnes turned much popular opinion against Philip and confused his contemporaries. They thought that the king must have been acting under the influence of an evil spell, as he kept Ingeborg imprisoned for the best part of twenty years.

To these examples of unhappy medieval royal unions could be added many others. For instance, Vojača of Bosnia (1417-ca. 1463) was repudiated for PR purposes by her husband Thomas once he gained the throne: she was thought to be too low-born to make a proper queen, and moreover she adhered to a heretical sect of Christianity. Jeanne of Valois (1464-1505) was of suitably royal birth, and was briefly queen of France in the 1490s. However her husband, Louis XII, had been forced to marry Jeanne against his will and so detested her. He forced her to undergo a trial in which he described in intimate detail the supposed physical deformities of Jeanne’s which made consummation of their marriage impossible—though Jeanne shot back fiercely that Louis was known to boast in the mornings of having “well earned a drink, for I mounted my wife three or four times during the night.”

A lack of sexual intercourse wasn’t what doomed other royal marriages. Juana of Portugal (1439-1475), queen of Castile, was banished from court by her husband, Enrique IV because the courtiers were abuzz with rumours that the royal couple’s sole child had actually been fathered by another man. Juana didn’t help her case by having two illegitimate sons with yet another lover, and Enrique successfully annulled the marriage in 1468.

And all that’s without invoking the shade of Henry VIII of England and his many wives.

None of this is to deny the significance of a divorced American of mixed-race heritage marrying into the British royal family. Some argue that Meghan Markle becoming the Duchess of Sussex has the potential to change popular perceptions of what it means to be British in the twenty-first century (though others are less optimistic). For a black woman to marry a member of the world’s most visible modern monarchy is empowering for many other black women, whose beauty and femininity are rarely validated by racist cultural stereotypes and beauty standards. Though the new duchess will be expected to be as silent, smiling, and dutiful as the other female members of the British royal family, the very fact that she as a black woman will be presented as an embodiment of “feminine” virtues is something new.

I’m also not trying to imply an unhappy fate for Meghan and Harry. As far as I can tell about two complete strangers, they seem very happy together and on a personal level I wish them well. But if their marriage succeeds, it won’t be because they enjoyed the pomp and circumstance of a royal wedding. For better or worse, their “happily ever after” will be made of the same stuff as that of any other couple.