We’re at that point in the semester when grading is making caffeine less a luxury and more a necessity, but when there also seems to be more and more to do on campus. I suppose in large part that’s because now that the Iowan winter is finally in retreat, it’s easier for people to make it here without through the snow. (Though this winter and spring, it’s been more the rain that we’ve had to worry about.)

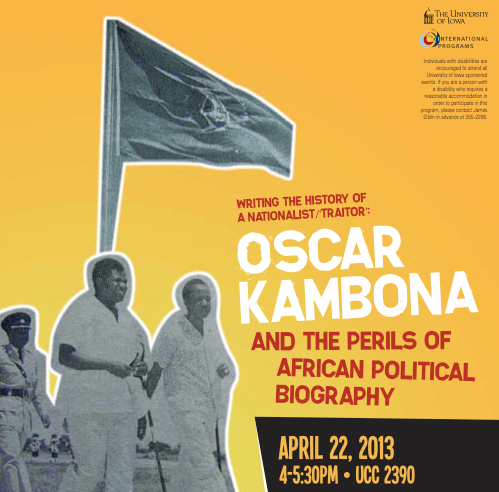

It makes for a busy schedule, though, which was why I was glad that some chai was served during this Monday’s lecture, given by James Brennan (Urbana-Champaign) on “Writing the history of a nationalist/’traitor’: Oscar Kambona and the perils of African political biography.” The history of sub-Saharan women and gender was one of my comprehensive exam fields, and between that and my trip there a couple of years ago, I’m quite interested in Tanzanian history—sadly, it’s not an interest I get to indulge much, between teaching and dissertation work. This means that I hadn’t heard of Oscar Kambona before Professor Brennan’s talk, but he was clearly a strange and fascinating figure.

Around the time of Tanzanian gaining its independence in the early 1960s, Kambona was the second most powerful man in the country, second only to the baba wa taifa—father of the country—Julius Nyerere. By ’64, Kambona was Minister for External Affairs and Defence, General Secretary of TANU and the Chairman of the OAU; within three years he was living in penurious exile in London, regarded in his home country at worst as a traitor, at best as the pioneer of his eponymous hairstyle. (While it looks quite innocuous nowadays, back in the day that strong side-part with a slight bouffant was apparently quite radical in Tanzania!) The circumstances of Kambona’s abrupt departure from the country are still murky—he may or may not have been involved in an attempted coup, though Prof. Brennan thinks it more likely that the root of the conflict between Kambona and Nyerere lay in the fact that the former was a “patronage” politican whereas the latter was a “conviction” politician.

Around the time of Tanzanian gaining its independence in the early 1960s, Kambona was the second most powerful man in the country, second only to the baba wa taifa—father of the country—Julius Nyerere. By ’64, Kambona was Minister for External Affairs and Defence, General Secretary of TANU and the Chairman of the OAU; within three years he was living in penurious exile in London, regarded in his home country at worst as a traitor, at best as the pioneer of his eponymous hairstyle. (While it looks quite innocuous nowadays, back in the day that strong side-part with a slight bouffant was apparently quite radical in Tanzania!) The circumstances of Kambona’s abrupt departure from the country are still murky—he may or may not have been involved in an attempted coup, though Prof. Brennan thinks it more likely that the root of the conflict between Kambona and Nyerere lay in the fact that the former was a “patronage” politican whereas the latter was a “conviction” politician.

What I found most fascinating was Brennan’s discussion of Kambona’s later years in exile, and of Brennan’s own process of researching those years, using papers still kept by Kambona’s family in London. Kambona seems to have spent his days petitioning people for money, and writing letters to various people in a code almost embarrassing in its lack of subtlety: “Oscar Wilde” needed thousands of dollars from his friends in Saudi Arabia to pay for “his sister’s wedding.” (The thoughts of Oscar being involved in political intrigues and coups made this Irishwoman laugh.) Brennan spoke of the possibilities created by focusing on dissidents or ‘traitors’ in part because to do so requires historians to think in terms of counterfactuals: the what ifs, the roads not taken. How much would a government headed by Kambona have shaped and changed the development of Tanzania? It’s an interesting mode of history, though one I think not often practiced by medievalists (at least not explicitly). Perhaps it’s because what actually did happen is often still opaque enough for us.

Prof. Brennan also spoke of the potential for unease inherent in accepting the generosity of Kambona’s family in giving him access to private papers and video tapes, in return for which he will publish work which may not present their father in the most flattering light. As someone who is primarily a medievalist, this is not an issue I have to deal with, by and large—studying nuns who’ve been dead for eight hundred years doesn’t require me to gain IRB approval. This is one of the reasons why I think an engagement with modern history is a good thing for a medievalist to do every now and then—it provides us with a little course corrective, a refresher, on the ethics of our practices as historians, a reminder of the duties we owe our subjects and our readers.