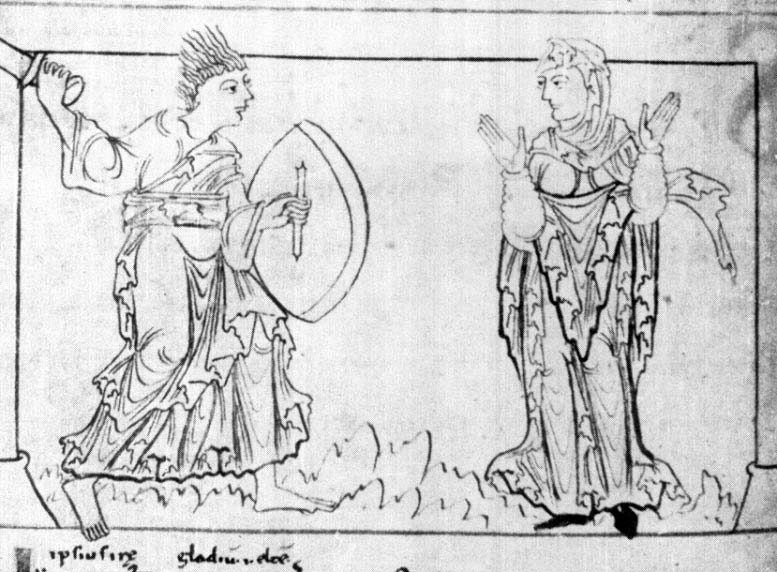

Image above: London, British Library MS Cotton Cleopatra C. VIII, f. 11. Ira (Anger), holding a shield, strikes with a sword at Patentia

Yesterday we had our second IFGM lecture of this semester, with Hilary Fox of the University of Chicago. While the transportation gods once more weren’t smiling on us—rush hour traffic and construction work—at least this time they conspired against us the night before the event, and not the day of, which was quite a help for my blood pressure!

One of the things which I like best about these lectures is how interdisciplinary they are, bringing together medievalists whose interests are highly diverse—really making the IFGM the forum that its name suggests. Both in our brown bag lunch with Hilary and at her talk itself, we got a real cross section of people from across the medievalist community here at the university, and it was good to meet new people and make new connections.

Hilary’s lecture, entitled “Eadswith’s Madness: Mental Illness, Self, and Community in Old English”, was an exploration of some issues which she hopes will be the basis of her next book project. She examined issues of mental disorder as understood by the Anglo-Saxons—in other words, not as we might nowadays classify mental disorder, because illnesses like epilepsy were considered to be disorders of the mind in early medieval England.

The human mind, for the Anglo-Saxons, was considered to be characterised by certain kinds of order—and losing those kinds of order, exhibiting traits which seemed to be common both to suffers of what we would now distinguish as neurological rather than mental illness, threatened to bring about a loss of self. Through a comparison both of literary tropes and of manuscript illustrations like the one above, from an Old English translation/transformative adaptation of the Psychomachia, Hilary demonstrated that for the Angl0-Saxons, their iconographies of anger and mental disorder overlapped to a very great extent. Both were capable of making humans into something quasi-bestial, as they destabilised the mind which was both the balancing point and the mediating link between the body and the soul. Hilary also looked at how issues of pastoral care, spatial identity, social roles and medical cures (including one striking example featuring a scourge made of cured dolphin skin!) factored into this.

All of this raises some fascinating questions about how the Anglo-Saxons theorised the body, and whether the concept of the “self” in vernacular writing really is something which emerges only in the later medieval period. The body is the tool with which you operate in the world, but it (you) also have some interior component, and these two parts of self interact in some interesting ways.

And yet I think for me the most valuable part of the talk and of the lively discussion which ensued was the reminder that we were looking not just at one way of theorising mental disorder, but multiple ways, some of which were even paradoxical, as writers struggled to reconcile differing conceptions of how mental disorder worked and what caused it (sin or an externalised demonic force, for instance). It was a salutary reminder that just as there may be multiple conflicting mainstream takes on an important issue nowadays, so to in the Middle Ages was there a great diversity of opinion. It seems such an obvious point, and yet I think one which we forget sometimes in our search for pattern and commonality.